We’ll need to review some of our OOP basics to prepare us for a discussion on variance. Hopefully, we can jog your memory and remember some of the fundamental principles of object-oriented programming.

OOP is boon to developers, because of it, we can write codes like this

val a:Int = 1

val b:Number = a

println("b:$b is of type ${b.javaClass.name}")

We can also write functions like this

foo(1) // (1)

foo(100F) // (2)

foo(120.0) // (3)

fun foo(arg:Number) { // (4)

println(arg)

}

(1) Int literal

(2) Float literal

(3) Double literal

(4) function Foo expects a Number, it can take Ints, Floats and Doubles. No Problem

The codes are possible because of the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP). It’s one of the more important parts of OOP — where a parent type is expected, you can use a subtype in its place. The reason we use a more generalized type (like Number, in Listing 7-9), is so that in the future, if we need to, we can write an implementation of a subtype and insert into an existing and working code. This is the essence of the Open Closed Principle (which states that a class must be open to extension but closed to modification).

NOTE The Liskov Substitution Principle and Open Closed Principle are part of the SOLID design principles. It’s one of the more popular sets of design principles in OOP. SOLID stands for (S) Single Responsibility (O) Open Closed (L) Liskov Substitution (I) Interface Segregation and (D) Dependency InversionLet’s take another example, see Listing 1

Listing 1. Employee, Programmer and Tester

open class Employee(val name:String) {

override fun toString(): String {

return name

}

}

class Programmer(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

class Tester(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

val employee_1 :Employee = Programmer("Ted") // (1)

val employee_2 :Employee = Tester("Steph") // (2)

println(employee_1)

println(employee_2)

}

(1) employee_1 is of type Employee, we’re assigning a Programmer object to it. Which is okay. Programmer is a subtype of Employee

(2) Same thing here, the type Tester is a subtype of Employee, so the assignment should be okay

No surprises here, the Liskov principle is still at work. Even if you put Programmer and Employee on a List, the type relationship is preserved.

Listing 2. Employee and Programmer in Lists

val list_1: List<Programmer> = listOf(Programmer("James"))

val list_2: List<Employee> = list_1

Listing 3. Group of Employees and Programmers

class Group<T>

val a:Group<Employee> = Group<Programmer>()

This is one of the tricky parts of generics. Listing 3 , as it currently stands, won’t work. Even if we know that Programmer is a subtype of Employee, and that what we’re doing is type safe, the compiler won’t let us through because the 2nd statement in the code above has a problem.

When you’re working with generics, always remember that by default Group, Group<Programmer> and Group<Tester> don’t have any type relationship — even if we know that Tester and Programmer are subtypes of Employee. By default, the type parameter in the class Group is invariant. For the 2nd statement (in Listing 3) to work, Group<T> has to be covariant. We’ll solve in Listing 4.

Listing 4. Classes Employee, Programmer, Tester and Group

class Group<out T> // (1)

open class Employee(val name:String) {

override fun toString(): String {

return name

}

}

class Programmer(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

class Tester(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

val a:Group<Employee> = Group<Programmer>() // (2)

}

(1) When you put the out keyword before the type parameter, that makes the type parameter covariant

(2) This code works because, Group is now a subtype of Group, thanks to the out keyword

From these examples, we can now generalize that if type Programmer is a subtype of Employee and Group is covariant, then Group<Programmer> is a subtype of Group<Employee>. Also, we can generalize that generic class, like Group, is invariant on type parameter, if for the given types Employee and Programmer, Group<Programmer> isn’t a subtype of Group<Employee>.

Now we’ve dealt with invariant and covariant. The last terminology we need to deal with is contravariant. If the type parameter of Group<T> is contravariant, for the same given types Employee and Programmer, then we can say that Group<Employee> is a subtype of Group<Programmer> — it’s quite the reverse of covariant.

Listing 5. Use the in keyword for contravariance

class Group<in T> // (2)

open class Employee(val name:String) {

override fun toString(): String {

return name

}

}

class Programmer(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

class Tester(name:String) : Employee(name) {}

fun main(args: Array<String>) {

val a:Group<Programmer> = Group<Employee>() // (2)

}

(1) The in keyword makes the type parameter contravariant, which means;

(2) type Group is now a subtype of Group

Subclass vs subtype

Alright. I suspect that what you’ve read in the last 10 minutes left a bitter taste in your mouth. How can it happen that Programmer is a subtype of Employee, List is a subtype of List but Group is not a subtype of Group<Employee>? Let’s try to answer that by going back to the concept of class, types, subclass and subtypes.

We think of a class as somewhat synonymous to a type, and generally that’s true — for non-generic classes at least, and for most of the time. We know that a class has at least one type, it’s the same type as that of the class itself. Go back to that time when you were first studying Java classes, your teacher, mentor or probably a favorite author must have defined a type of an object like this — “it’s the sum total of all its public behavior, otherwise known as the object’s methods or contract” — or something like that; let’s just say it’s the set of behavior that the object has.

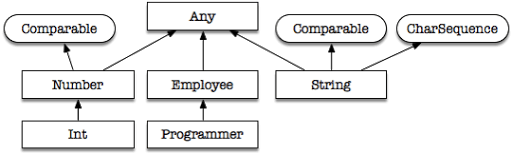

Going back to “a class has at least one type”, well, it can have more. Just look at Figure 1.

From Figure 1, we can say

- Any is at the top of the class chart — class Any is the equivalent of java.lang.Object

- Employee is a subclass of Any. Employee has two types, the one that it inherited from Any, and itself — because the Employee class can define its own set of behavior (methods), so that counts as one type

- Programmer is a subclass of Employee which is a subclass of Any, which means Programmer has 3 types. One from Any, another from Employee and another coming from the Programmer class itself

- Number is a subtype of Any, but it also implements the Comparable interface. So, Number has 3 types, one from Any, another one from itself and another from the Comparable interface. We can say that Number is a subtype of Any and it’s also a subtype of Comparable — whatever you expect the Comparable to do, the Number can do, whatever Any can do, Number can also do. This is basic OOP

- The String class has 4 types. One from Any, another from Comparable, another one from CharSequence and lastly, from its own class

From the statements and the diagram above, it’s okay to use subclass and subtype interchangeably. There’s not much difference between the two. Their difference will become apparent when we start considering nullable types.

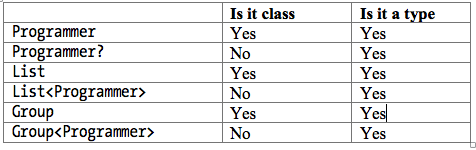

The case of the nullable type is an example where a subclass is not the same as a subtype. See Figure 2.

When you put a question mark after the name of a type, it becomes the nullable version of that type. In Kotlin, we can create two types from the same class — the nullable and the non-nullable version. We can’t really say Programmer is a subclass of Programmer? because there is just one class definition for Programmer, but Programmer (the non-nullable version) is a subtype of Programmer? (the nullable one). Similarly, Any is a subtype of Any? but Any? is not a subtype of Any — the reverse direction isn’t true.

It’s okay to write this

var j:Programmer? = Programmer("Ted") // assign non-null to nullable Programmer

j = null. // then we assign a null to j

But it’s not okay to write this

var i:Programmer = j // assign j (which is null) to non-nullable Programmer

Now we come to generics. Figure 3 should help us illustrate the next set of concepts we need to grapple with.

We know the first relationship, Employee is the supertype of Programmer. We also know List<Employee> will accept List<Programmer>, we tested this in Listing 2 — you’re probably not quite sure why it works, so, I’ll circle back to this point after we deal with the third set of boxes.

Now, given the codes

class Group<T>

val a:Group<Employee> = Group<Programmer>() // not sure

Why is it that we can’t reliably answer the question “is Group<Employee> a supertype of Group<Programmer>”.

It’s because, while Group is a class, Group<Employee> is not, and by extension,Group<Programmer> is not a subclass of Group<Employee> — if you’re thinking of List<Employee> and List<Programmer> right now, stop. I did say I’ll circle back to that. Stick with Group<Employee> and Group<Programmer> first. Table 1 should help us summarize some of these things.

Now we can establish that Group<Employee> has no type relationship with Group<Programmer> even if class Employee has a type relationship with Programmer. The type parameter in Group<T> is by default, invariant (no type relationship). In order to change the variance of you need to use either out (to make it covariant) or in (to make contravariant) keyword.

So, if we want Group<Programmer> to be a subtype of Group<Employee> we need to write the Group class like this

class Group<out T>

val a:Group<Employee> = Group<Programmer>() // this is ok now

Now we can circle back to List<Employee> and List<Programmer> question. Why and how does it work. Why is it okay to write this

var m:List<Employee> = listOf(Programmer("Ted"))

The simple answer lies in the definition of the List interface, I copied the source code of the List interface in Listing 6 for your convenience; I stripped all the comments.

Listing 6, List interface (excerpt)

public interface List<out E> : Collection<E> { // (1)

override val size: Int

override fun isEmpty(): Boolean

override fun contains(element: @UnsafeVariance E): Boolean

override fun iterator(): Iterator<E>

override fun containsAll(elements: Collection<@UnsafeVariance E>): Boolean

public operator fun get(index: Int): E

public fun indexOf(element: @UnsafeVariance E): Int

public fun lastIndexOf(element: @UnsafeVariance E): Int

public fun listIterator(): ListIterator<E>

public fun listIterator(index: Int): ListIterator<E>

public fun subList(fromIndex: Int, toIndex: Int): List<E>

}

(1) Type parameter is covariant. List uses the out keyword before the type parameter E

The reason why it’s okay to assign List<Programmer> to List<Employee> is because the type parameter on List<E> is covariant. Hence, if type Employee is a supertype of Programmer, and List<E> is covariant, then List<Programmer> is a subtype of List<Employee>.

So, now that we understand types and subtypes a bit better, like in a Quentin Tarantino movie, I’d like you go back to the beginning of the article and give it another read. I hope it'll make better sense by then.

(shameless plug) This article is lifted from chapter 7 of Learn Android Studio 3 with Kotlin.