Last week you probably were bombarded with articles, videos, and tweets about how microservices were dead and how Amazon killed them. This all stemmed from a blog post they published in March, sharing how they cut 90% of their costs by migrating their microservices architecture to a monolith. You can read their full blog post here. Here I'll dive into what that means and why that matters. But what really has surprised me is that people only recently started talking about it, even though it's something they shared with the world well over a month prior.

Not to be a conspiracy theorist, but this change doesn't matter to most developers, and I believe the hype around this is being manufactured. Every decision we make when building something has trade-offs, and you only realize some of the costs, financial and regarding efficiency, once you build it.

What Happened at Amazon?

Amazon's Prime Video serves thousands of live streams to their customers. To ensure an excellent experience for all of them, they needed a tool to monitor stream qualities and try to fix streams whenever issues arose. The Video Quality Analysis (VQA) team at Prime Video had a tool to handle this, but it was never meant for scale, and as they onboarded more and more streams, the issues of costs and bottlenecks began to pop up.

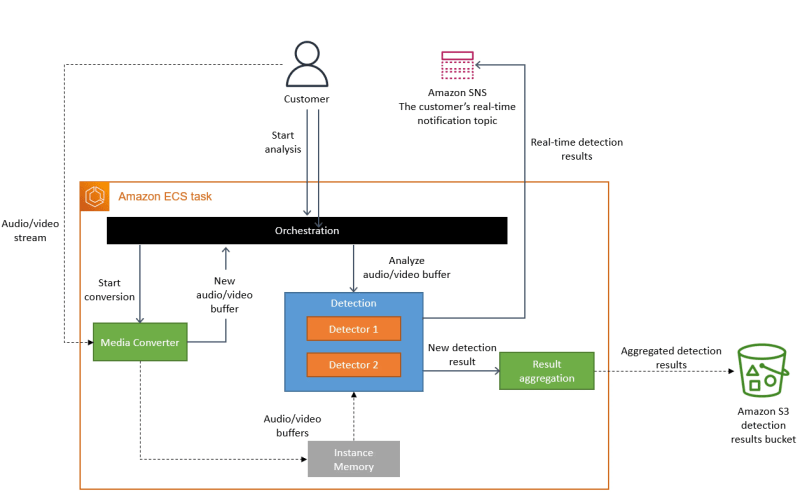

Amazon's tool was broken into three main components: the media converter, defect detectors, and orchestration. The media converter ran as an AWS Lambda function, converted audio and video streams, and stored the data in an S3 bucket. The defect detectors, also running as an AWS Lambda function, would pull the parsed data from the S3 bucket and analyze the frames and audio for any issues. Finally, the orchestration controlled the system's flow using Amazon's AWS Step Functions.

This diagram shows Amazon's serverless architecture for monitoring their video streams.

Backend developers may already start to see the problem. But, if it's not clear, let's break it down...

Why AWS Step Functions Didn't Work

While AWS Step Functions makes managing a workflow easier, that ease of use comes at a price. Prime Videos' service performed multiple state transitions every second. Each state transition had a cost ($0.025 per 1,000 state transitions). They were also being throttled, as making so many requests per second per stream caused them to quickly hit their account limit.

Why Amazon S3 Didn't Work

Every read and every write to a cloud storage bucket has a cost. Let's say the media converter writes about 24 blobs of image data to the S3 bucket per second. For 1000 streams, that is 24,000 writes per second. Assuming approximately 2,937,600 seconds in a month would total about 70,502,400,000 writes of image data. Remember the audio data; that brings us up to 141,004,800,000 writes monthly. Oh! The defect detector also has to read all of that data too. So we also have 141,004,800,000 reads monthly.

That's just the reads and the writes in a month, and my mind is already boggled. Putting the reads and the writes into the AWS Pricing Calculator costs $761,425.92 a month, and that's just the reads and the writes; we haven't even begun to consider the actual data stored itself!

What Amazon Did

Splitting up the parsing and inspection of the video streams was a massive money-burning endeavor, but the core workflow they had orchestrated was logical. So they undertook the gigantic endeavor of rearchitecting their infrastructure by merging the different services into one process.

Amazon said, "We realized that distributed approach wasn't bringing many benefits in our specific use case." So, they decided to rearchitect the system into a monolith.

The core logic of their media converter and defect detector microservices was sound. So conceptually, their high-level architecture was able to remain the same. Keeping the same three components of the initial implementation, they reused much of their code to quickly migrate to the new monolithic architecture.

Now that their media converter and defect detector ran on the same server, there was no longer a need for an intermediary that would store the parsed video and audio data. This eliminated the need for an intermediate storage system, saving them money reading, writing, and storing data on their S3 bucket.

The only new piece they would need to implement is an orchestration layer for their single application that managed the different components; this removed the costs and limitations of AWS Step Functions.

This diagram shows Amazon's new architecture for their monitoring service.

Does Any of This Matter?

Honestly, probably not. It's not to say that it's not interesting, but rather their use case is very abnormal compared to many other companies and developers trying to build infrastructure that scales. Keep in Amazon is maintaining thousands of streams every second. This scale and requirements only apply to FAANG companies. When thinking about companies where streaming and streaming quality come to mind, the immediate two are Twitch and YouTube, owned by Amazon and Google. It probably doesn't affect you if you're not in that business.

Stealing from a close friend of mine, "the most efficient cost savings for your company are simply to either A) Consolidate your microservices fleet B) Consolidate your disparate data sources or C) Drop some services altogether." He explains that the hardest thing to do is identify which of these three points should be prioritized, and he's right.

As a separate rant on my end, reviewing how they structured their system, they opted for the easiest tools with the highest costs.

Serverless functions follow a pay-per-use model where you're only billed for the actual time your functions execute. The idea is that this is more cost-effective when compared to dedicated servers because you can always wind down functions when they're not being used. The catch is that the time to process/compute on a serverless function is likely more than on a dedicated server, but because it only runs when needed, you can save money because you don't need to be running them all the time.

But here, that's a wasted benefit as these functions are executed multiple times per second, every second, managing a live video stream. The media converter and defect detectors could have likely been run on their own EC2 instances. They would have had their always-running, scalable servers, like AWS Lambda. Though the issue of storage between services would still remain.

When it comes to the limitations of AWS Step Functions, let us look at what it was doing. Step Functions handled communication between the different steps of their stream quality architecture and error handling. When it comes to communication between services, tools like Kafka exist and can be used to transfer data (or state) between services. Kafka uses a pub/sub (publish and subscribe) messaging model that allows producers to publish topics to consumers, that can then act on the topics they are subscribed to. Kafka's pub/sub model allows for efficient and reliable data streaming, making it perfect for building event-driven systems, such as one that handles monitoring video quality.

There are obvious limitations and concerns with my off-the-cuff solution. Such as the need for a storage bucket to share video and audio data between services, but I bring them up to show that from the beginning, the tools used to build the stream monitoring system weren't built for scale. And the Prime Video team was aware of this from the get-go. According to Marcin Kolny, a Senior SDE at Prime Video, they "designed [their] initial solution as a distributed system using serverless components, which was a good choice for building [their] service quickly." But they knew they would hit limitations from their initial design; they didn't think it would happen so soon.

What You Should Take From This

Whether you build your system using microservices or a monolithic architecture should be on a case-by-case basis. Every company's needs are different, and careful consideration should be made.

On the other side of the video streaming world is Netflix, which pioneered microservice architecture. In 2008, Netflix dealt with a database corruption that took them four days to resolve, as their services depended on each other. Even though it was a database failure, they had to fix all their other services. After that experience, they opted to migrate to microservices and now run close to 1,000 microservices, each managing a part of their business and services. (Source)

Remember that this monolith application only handles one component of its entire Prime Video services. Other elements of Prime Video, as well as core Amazon, continue to use microservice architectures. The need for this transition boiled down to bottlenecks in their tools and the cost of constantly reading and writing to an S3 storage bucket.

At the end of the day, consider what you're looking to do and how you'll be using resources, whether that's storage, compute time, RAM, or anything else. While you may look to save money here and there, you also want to ensure you're building with tools and systems that can scale, are reliable, and are easy to maintain.

Wrapping Up

The reports of microservices' death are greatly exaggerated. And we'd all be wise to remember that when building a new project, it's essential to consider your project needs.

If you're interested in learning more about microservices, I wrote an introductory blog post you can find here.

Whether you build your next project as a monolith or with microservices, check out Amplication. Amplication helps developers build backend services quickly using the highest standards that are consistent and scalable.

If you like the work we do, be sure to give us a 🌟 on GitHub and join our Discord community to chat with other Amplication developers.