Teaching Numbers How To Sing

Everything is music. When I go home, I throw knickers in the oven and it's music. Crash, boom, bang!

- Winona Ryder as Björk on SNL's Celebrity Rock 'N' Roll Jeopardy! - 2002 - YouTube

In this post, we'll throw something random into, well, a math-oven and viola, music! We'll just skip the crash.

In other words, we're going to teach our computers to "sing" using idiomatic Rust, backed by a little light physics and music theory.

The one-liner in the cover image procedurally generates a melody using tools assumed to be present on a standard desktop Linux distribution like Ubuntu. The melody produced will be composed of notes along a single octave in a hardcoded key (A major):

By the end of this post our program will:

- Support 86 different key signatures with minimal effort.

- Support a full 108-key extended piano keyboard, allowing the user to pick a range.

- Produce any arbitrary tone we ask for.

- Compile and run on Windows, MacOS, or Linux with no extra code (I tried all three).

- Encourage further extension with lots of Rust-y goodness.

C# minor has a funky, dark kind of vibe - Lullaby by The Cure, Message in a Bottle by The Police, Feel It Still by Portugal, The Man, a bunch of others. Your computer could be the next Dolly Parton (Jolene):

$ ./music -b C#2 -o 4 -s minor

.: Cool Tunes :.

Generating music from the C# minor scale

Octaves: 2 - 6

[ C# D# E F# G# A B C# ]

However, at the end of the day, it's just the thing in the cover image.

While the complete runnable source code is embedded within this post, the full project can also be found on GitHub along with some pre-compiled binaries. Feel free to make a PR!

Table of Contents

- Preamble

- The Meme

- The Program

- Challenges

Preamble

This tutorial is aimed at beginners (and up) who are comfortable solving problems with at least one imperative, object-oriented language. It does not matter if that's JavaScript or Python or Object Pascal, I just assume you know the basic building blocks of creating a program in an object-oriented style. If you already know Rust some of this will be skimmable, but this is primarily a post about the problem space and not "how to use Rust".

You do not need any prior knowledge of physics or music theory, but there will be a tiny smattering of elementary algebra. I promise it's quick.

I have two disclaimers before getting started:

- There are 257 links here, 199 of them to Wikipedia. If you're that kind of person, set rules.

- Further to Point 1, most of this I learned myself on Wikipedia, some of it while writing this post. The rest is what I remember from high school as a band geek, which was over ten years ago. I do believe it's generally on the mark, but I am making no claims of authority. If you see something, say something.

The Meme

This post was inspired by this meme I saw when I was attempting to casually browse Reddit:

I couldn't let myself just scroll past that one, clearly. Here's a version of the bash pipeline at the bottom with slightly different hard-coded values, taken from this blog post by Robert Elder that explores it:

cat /dev/urandom | hexdump -v -e '/1 "%u\n"' | awk '{ split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,","); for (i = 0; i < 1; i+= 0.0001) printf("%08X\n", 100*sin(1382*exp((a[$1 % 8]/12)*log(2))*i)) }' | xxd -r -p | aplay -c 2 -f S32_LE -r 16000

The linked blog post is considerably more brief and assumes a greater degree of background knowledge than this one, but that's not to discredit it at as a fantastic source. That write-up and Wikipedia were all I needed to complete this translation, and I had absolutely not a clue how this whole thing worked going in.

I've gotta be honest - I didn't even try the bash and immediately dove into the pure Rust solution. Nevertheless, it serves as a solid 30,000ft roadmap:

-

cat /dev/urandom: Get a stream of random binary data. -

hexdump -v -e '/1 "%u\n"': Convert binary to 8-bit base-10 integers (0-255). -

awk '{ split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,","); for (i = 0; i < 1; i+= 0.0001) printf("%08X\n", 100*sin(1382*exp((a[$1 % 8]/12)*log(2))*i)) }': Map integers to pitches and return sound wave samples. -

xxd -r -p: Convert hexadecimal samples back to binary. -

aplay -c 2 -f S32_LE -r 16000: Play back binary samples as sound wave.

Don't worry at all if some or all of this is incomprehensible. You don't need to have a clue how any of it works yet. This program is not a direct translation of that code, and I'm not going to elaborate much on what any of the specific commands in the pipeline mean (read the linked post for that), just the relevant logic. By the time we're done, you'll be able to pick apart the whole thing yourself.

If you'd like the challenge of implementing this yourself from scratch in your own language, stop right here. If you get stuck, this should all apply to whatever you've got going unless you've gone real funky with it - in which case, it sounds cool and you should show me.

The Program

Project Structure

Before getting started, ensure you have at least the default stable Rust toolchain installed. If you've previously installed rustup at any point, just issue rustup update to grab the latest stable build. This code was written with rustc version 1.39.0 (released November 4, 2019), but should compile on any version compatible with Rust 2018.

Then, spin up a new library project:

$ cargo new music --lib

Open your new music project directory in the environment of your choice. If you're not already sure what to use with Rust, I recommend Visual Studio Code with the Rust Language Server installed for in-editor development support. If you have rustup present, the VS Code RLS extension has a one-click set up that's worked for me without a hitch on both Linux and Windows 10.

Dependencies

We'll use a few crates, which is the Rust term for external libraries. Two of them give us functionality not found in the Rust standard library:

rand is in place of /dev/urandom, and rodio will cover and aplay. We can replace hexdump, xxd, and the awk logic built-in stuff. The rand crate provides several different random number generators (RNGs), and the one perfect for this application isn't included by default. We have to specifically add it to the configuration, so its declaration is split out to deifne multiple keys.

The other two are just for programmer comfort. I also use pretty_assertions to make the test runner output a little prettier and structopt to get a minimal-effort CLI.

In Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

rodio = "0.10"

structopt = "0.3"

# the section below is equivalent TOML to:

# rand = { features = [ "small_rng" ], version = "0.7" }

# it's a style preference

[dependencies.rand]

features = [ "small_rng" ]

version = "0.7"

[dev-dependencies]

pretty_assertions = "0.6"

Test Driven Development

Cargo has auto-created a file at src/lib.rs to define your library, but hold on - we're going to write this program using Test-Driven Development, or TDD. This means we're going to define the expected behavior of new functionality before attempting the implementation. Here's an example of a test we'll write later:

#[test]

fn test_add_interval() {

use Interval::*;

assert_eq!(Unison + Unison, Unison);

assert_eq!(Unison + Maj3, Maj3);

assert_eq!(Maj2 + Min3, Perfect4);

assert_eq!(Octave + Octave, Unison);

assert_eq!(Tritone + Tritone, Unison);

assert_eq!(Maj7 + Min3, Maj2);

}

Each test is just a plain Rust function. In it we use a feature of our library and assert that the result matches the expected result that we hardcode. In this test, we're specifying the expected behavior when adding musical intervals together with the + operator. This way, we can tell immediately if the code we write actually matches the specification. As our code evolves we'll immediately notice if we break functionality that worked previously.

The Rust toolchain has a test runner built-in, so this all works out of the box. Every function marked #[test] will be executed during an invocation of cargo test, so we can see anywhere our expectations are not met in the whole program.

All of our tests will live in their own separate module. Create a new file at src/test.rs:

use super::*;

use pretty_assertions::assert_eq;

#[test]

fn test_cool_greeting() {

assert_eq!(GREETING, ".: Cool Tunes :.");

}

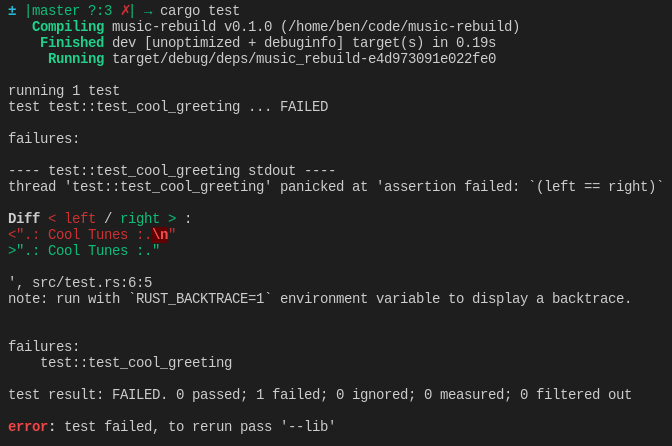

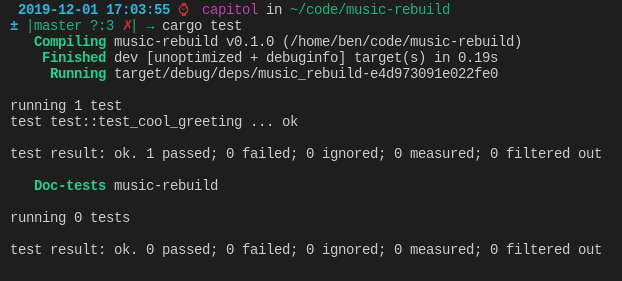

If the two arguments to assert_eq!() are not equal, this test will fail and you'll get pretty-printed output showing you the difference between the two. I generally put the test code in the first argument and the hardcoded expected value in the second.

This test is importing a constant, GREETING, from our library, and expecting it to be the string Cool Tunes (tm). This code will fail to compile, though - there's no such super::GREETING constant available to test! The super part means "one module higher" - test is a child module of the music library we're writing, so the crate root in lib.rs corresponds to super here. You could also say crate::* or music::*. Now open up src/lib.rs and replace the contents with this:

#[cfg(test)]

mod test;

pub const GREETING: &str = ".: Cool Tunes :.\n";

The #[cfg(test)] tag tells the compiler to only build the test module when we're using the test runner. The compiler won't even look at it when using cargo run.

Now we can give cargo test a go - the first build will take the longest as it gathers and builds dependencies for the first time:

Whoops - no need to include a newline with the greeting string, we'll pass it to println!() in the program which includes one:

#[cfg(test)]

mod test;

- pub const GREETING: &str = ".: Cool Tunes :.\n";

+ pub const GREETING: &str = ".: Cool Tunes :.";

Let's try this again:

Good to go! Throughout this post new sections of code will be preceded by a test with he #[test] tag that defines the behavior we're aiming for. These tests should all go in src/test.rs.

Entry Point

Finally, create a directory called src/bin. This optional module is where Cargo will by default expect an executable, if present. Place a file at src/bin/music.rs - this filename will be the name of the executable, so when distributed you'd execute ./music to run the code in main():

use music::*;

fn main() {

println!("{}", GREETING);

}

Give it a go with cargo run:

$ cargo run

Compiling music-rebuild v0.1.0 (/home/you/code/music)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.16s

Running `target/debug/music`

.: Cool Tunes :.

The coolest tunes. You can see right above the output the actual name of the executable file being run - you can find it right in your project's target directory:

Your music/src directory should look like the following:

~/code/music $ tree src

src

├── bin

│ └── music.rs

├── lib.rs

└── test.rs

1 directory, 3 files

This is a good time for an initial commit:

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Initial Commit"

You can run a faster compilation pass with cargo check if you just want the compiler to verify your code's integrity, not produce a binary.

Traits

If you're already familiar with developing in Rust, you can probably skip right to Random Numbers.

If you are brand new to the language, you should expect to spend a little longer with the code in this post to extract the relevant bits. I'm not going to devote much time in general to Rust-specific topics, as there is a vast amount of great material already available devoted to that, but out of all of Rust's interesting properties this is the big one you'll need to know about to follow along with this program.

Most of this code is compartmentalized using Rust traits, which collect bits of composable functionality (my type "has-a" ScreenWidget trait that implements those methods). It's OOP, Jim, but not as we know it. In this post, you can think of them like interfaces in more traditional class-based OOP languages. They're a little more powerful, but that analogy does fit and is enough to get you up and running.

One big difference from "regular" object-oriented programming is that this is all we get. There's no such thing as inheritance (my type "is-a" more specific ScreenWidget type and inherits or overrides those methods). As a result, composition of functionality features heavily in Rust code in the form of impl SomeTrait for MyType {} blocks, with collections of method definitions inside.

The compiler can infer types in many situations, and can auto-fill these trait implementations for us in many cases with a #[derive(..)] tag. In this case, the default value is also the Default value for the primitive type i32, which for all the numeric types is 0 (or 0.0). When that's what we want in this context too, we can ask the compiler to auto-generate the above code with this syntax:

#[derive(Default)]

struct MyType {

value: i32,

}

Writing this code is nearly equivalent to the former in terms of the output machine code. This syntax is a macro that will expand to the full Rust code for any impl Trait block being derived blocks before your program is compiled as if it had been fully written out. In general, a struct can derive a trait as long as all of its members implement that trait, either derived or hand-implemented, because the compiler will just call that method for whatever type it needs. The auto-derived Default implementation looks like this when your code reaches the compiler:

impl Default for MyType {

fn default() -> Self {

Self { value: i32::default() }

}

}

Now we can use MyType::default() to construct an object of this type - the following two statements store the same object to obj:

let obj = MyType::default();

// or

let obj: MyType = MyType { value: 0 }

It's up to the specific type to decide what happens, as long as the input and output types match. Whenever you get lost just remember - it's traits all the way down.

We can also define methods that aren't associated with any trait with, e.g.:

impl MyType {

fn some_specific_thing(&self) {

// ..

}

}

Random Numbers

The first part of the one-liner is cat /dev/urandom | hexdump -v -e '/1 "%u\n"', which gets a source of random bytes (8-bit binary values) and shows them to the user formatted as base-10 integers.

When I sat down to write this program, I decided to knock out this functionality first mostly because I immediately knew how. The rand crate can give us random 8-bit integers out of the box by using the so-called "turbofish" syntax to specify a type: random::<u8>() will produce a random unsigned 8 bit integer (u8) with the default generator settings.

To match the one-liner exactly, we could write an Iterator implementation with a next() method like this - no need to copy this code to your project, we don't use it again:

impl Iterator for RandomBytes {

type Item = u8;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> {

Some(random::<Self::Item>())

}

}

If we endlessly call this method, we'll get output that matches cat /dev/urandom | hexdump -v -e '/1 "%u\n"' exactly:

fn main() {

let mut rands = RandomBytes::new();

loop {

println!("{}", rands.next().unwrap());

}

}

I'm not bothering to show you the full runnable snippet - try to build the RandomBytes struct yourself if you'd like. In a bash one-liner you've got to take your randomness where you can get it, but the rand crate provides a richer set of tools. Before streaming in something random, we need to think about what exactly it is we're randomizing.

In this application, we want to pick a musical note from a set of valid choices at random. The awk code does this with the modulo operator: list[n % listLength]. That will take a random index that's ensured to be a valid list member. See if you can spot the corresponding section of the cover image code.

We get to use the rand::seq::SliceRandom trait here. This gives us a choose() method that we can call on any slice to pull a random member.

So, there's no need for a RandomBytes iterator. Instead, we need to define a list of notes and call [notes].choose(&mut RNG) on it to get a specific note to play.

Mapping Numbers To Notes

Take a closer look at step 3 of the pipeline. This code closely resembles the core logic we ultimately end up with:

split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,",");

for (i = 0; i < 1; i += 0.0001)

printf("%08X\n",

100 * sin(1382 * exp((a[$1 % 8] / 12) * log(2)) * i))

This is probably still not too helpful for most - there's magic numbers and sines and logarithms (oh, my) - and its written in freakin' AWK. Don't despair if this still doesn't mean much (or literally anything) to you.

We can glean a bit of information at a glance, though, and depending on your current comfort with this domain you may be able to kind of understand the general idea here. It looks like we're going to tick up floating point values by ten-thousandths from zero to one (0.0, 0.0001, 0.0002, etc.) with for (i = 0; i < 1; i += 0.0001), and do... I don't know, some math on each value. In that math we're using both i, the current fractional part from 0 to 1, and $1, which is the random 8-bit integer being piped in. Specifically, we're indexing into a list a: a[$1 % 8]. In other words, we're using the random byte 0-255 to select an index 0-7 from this list.

The list is defined with split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,",");, which means split the first parameter string input by the third parameter ",", and store the resulting list of elements to the second parameter a (awk is terse). After we do the math, we're going to print it out as an 8-digit hex number: printf("%08X\n", someResult) - this printf formatter means we want a 0-padded number that's 8 digits long in upper-case hexadecimal. The base 10 integer 42 would be printed as 0000002A.

TL;DR for each ten-thousandth between 0 and 1 i, select a value n from [0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12] and return the result of 100 * sin(1382 * exp((n / 12) * log(2) * i).

If you recognize this formula, awesome! You can probably skim the next section. If not, it's still not time to panic. We just need to get some fundamentals out of the way.

A Little Physics

Sound is composed physically of vibrations. These vibrations cause perturbations in some medium, which radiate out from the source of the vibration, and those perturbations cause tiny oscillating variations in local atmospheric pressure. These variations are what we experience as sound. When we're talking about hearing a sound with our ears, the medium is usually air.

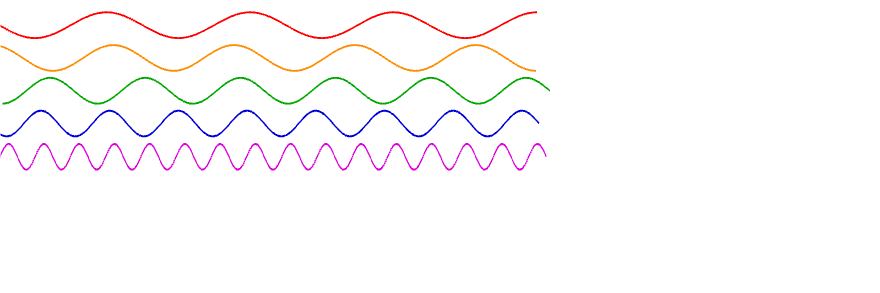

Sine Waves

Sound propagates as a wave. In reality a sound contains many components but for this program we can talk about a super-simplified version that can be represented as a single sine wave:

If the x-axis is time, a sine wave represents a recurring action with a smooth (or analog) oscillation between peaks. Lots of physical phenomena are analog in nature - picture a ball getting tossed, rising and then falling. The ball passes through every point in between the highest point it hits and the ground, so we can measure at any arbitrary instant an exact fractional height. It doesn't fall from 8 meters to 7 meters all at once, it passes through 7.9, 7.8, 7.7, and all infinitesimally small heights in between too. It's the same with sound.

Instead of height above the ground on the y axis, we have a pressure gradient from an equilibrium. The air is getting rapidly pushed and pulled by this vibration across space as a wave. It's still a physical phenomenon - a pressure gradient rises to a peak and then falls back to equilibrium and then below to an opposite peak, oscillating back and forth. It doesn't just magically become a different higher value all at once. A guitar string wobbling passes through each point in space between the two extremes it's tensing to and from, so the vibrations it causes oscillate in kind.

You can actually use math to represent multi-component sound waves as a single wave - the ability to do so is what enables the whole field of telecommunications. We're not going to touch that today, partially because I don't actually know how to perform a Fourier transform myself (yet). One single sine wave is enough of a signal to produce a tone, so we can keep it simple.

There are two interesting properties of a sine wave: the amplitude, which measures the current deviation from the 0 axis for a given x, and the frequency, which is how close together these peaks at maximal amplitudes are, or how frequently this recurring thing happens. The combination of the two dictate how we perceive the sound. The amplitude will be perceived as volume and the frequency as pitch.

You can do cool things like frequency modulation and amplitude modulation to encode your signal as modulations of one of these properties:

This is how FM and AM radio process incoming sound signals to broadcast them to your radio, which can then perform the reverse and play back the original sound. We also don't do any of that today, but you could experiment with these functions with this as a base.

Pitch

The standard unit for frequency is the Hertz, abbreviated Hz, which measures the number of cycles per second. One cycle here is the distance (or time) between two peaks on the graph, or the time it takes to go all the way around the circle once:

According to my super scientific smartphone stopwatch observations, this gif is chugging along at a whopping 0.2Hz.

Recall above that we saw we're going to run a loop like this: for (i = 0; i < 1; i += 0.0001). In that loop, the math we process includes the function sin(). If one were to, say, calculate a bunch of points along a single cycle of a sine wave like this one, it sure seems like just such a loop could get the job done.

The higher the frequency, or closer together the peaks representing maximum positive amplitudes, the higher the pitch.

Sound is a continuous spectrum of frequency, but when we make music we tend to prefer notes at set frequencies, or pitches. I'm using fundamental frequency and pitch interchangeably, because for this application specifically they are, but go Wiki-diving if you want to learn about the distinction and nuance at play here. The nature of sound is super cool but super complex and outside of the scope of this post - we just want to hear some numbers sing, we don't need to hear a full orchestra.

One of the super cool things about it is the octave. Octaves just sound related, you know?

It turns out the relationship is physical - to increase any pitch by an octave, you double the frequency. Not only that, this fixed ratio actually holds for any arbitrary smaller or larger interval as well. This system is called "equal temperament" - every pair of adjacent notes has the same ratio, regardless of how you define "adjacent". To get halfway to the next octave, you multiply by 1.5 instead of 2.

To start working with concrete numbers, we need some sort of standard to start multiplying from. Some of the world has settled on 440Hz - it's ISO 16, at least. It's also apparently called "The Stuttgart Pitch", which is funny.

We can keep track of Hertz with a double-precision floating-point value:

#[derive(Debug, Default, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, PartialOrd)]

pub struct Hertz(f64);

This is just a floating point value, but I didn't just assign an alias like type Hertz = f64. Instead, I made my very own fully-fledged new type. A lot of this program will involve type conversions and unit conversions, but they will all be explicit and defined in places we expect. When manipulating our increasing set of abstractions we don't want to have to think about things like floating point accuracy - it should just work as we expect. The tuple struct syntax is perfect for this, when the underlying value is just a single value but there may be complex relationships with other types.

Luckily, the compiler can actually derive a number of things for us straight from the inner value. For the rest, we'll provide our own implementations that destructure the tuple:

#[test]

fn test_subtract_hertz() {

assert_eq!(Hertz(440.0) - Hertz(1.0), Hertz(439.0))

}

use std::ops::Sub;

impl Sub for Hertz {

type Output = Self;

fn sub(self, rhs: Self) -> Self::Output {

Self(self.0 - rhs.0)

}

}

This allows us to subtract two Hertz values with the subtraction operator -, and get a Hertz back. We can also give ourselves some more helpful conversion traits - this gets us both the defined from() and the type-inferred into() in both directions with f64:

impl From<Hertz> for f64 {

fn from(h: Hertz) -> Self {

h.0

}

}

impl From<f64> for Hertz {

fn from(f: f64) -> Self {

Self(f)

}

}

There are a lot of unit conversions throughout this program but all of them are explicit and defined where we expect them. This does add to our boilerplate, but reduces the element of surprise - my LEAST favorite element in programming. Next, we need a way to represent a pitch:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, PartialOrd)]

pub struct Pitch(Hertz);

I didn't take Default this time - the default pitch is not 0Hz. We want our new Pitch type to default to A440, but also accept any arbitrary value:

#[test]

fn test_new_pitch() {

assert_eq!(Pitch::default(), Pitch(Hertz(440.0)));

assert_eq!(Pitch::new(MIDDLE_C), Pitch(Hertz(261.626)));

}

The following code gets us there:

pub const STANDARD_PITCH: Hertz = Hertz(440.0);

pub const MIDDLE_C: Hertz = Hertz(261.626);

// ..

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, PartialOrd)]

pub struct Pitch(Hertz);

impl Pitch {

pub fn new(frequency: Hertz) -> Self {

Self(frequency)

}

}

impl Default for Pitch {

fn default() -> Self {

Self(STANDARD_PITCH)

}

}

Verify it all with cargo test:

running 3 tests

test test::test_cool_greeting ... ok

test test::test_subtract_hertz ... ok

test test::test_new_pitch ... ok

test result: ok. 3 passed; 0 failed; 0 ignored; 0 measured; 0 filtered out

I won't keep prompting you to do so, but the prevailing wisdom is to run it after adding every test and watch it fail even before adding the implementation. Then you can watch it fail in incrementally different ways as you get closer to the correct code.

Singing

Knowing what frequency to use to produce a given pitch is all well and good, but we need to actually make the sound. When we sing with our voice, our speech organs vibrate to produce complex multiple-component sound waves of differing frequencies. We can program ourselves a little one-frequency "speechbox" that produces a wave programmatically instead of by physically vibrating.

To do so, we're going to perform an analog-to-digital conversion. That's a super fancy term for something that isn't that complicated conceptually. We're going to graph the function of a single cycle of the target sine wave and sample it. If you already know how we're doing this part, feel free to skip this explanation.

A sine wave, as we've seen, is smooth. However, what's a graph but a visualization of a function. There's some function mySineWave(x) that's this wave when we put in a bunch of fractional numbers between 0 and 1. The for (i = 0; i < 1; i += 0.0001) loop is doing exactly that, calculating a series of adjacent points at a fixed interval (0.0001) that satisfy the function of this wave. That's our analog-to-digital conversion - we've taken something smooth, a sine wave, and made it digital, or made up of discrete points. For Pitch::default(), this cycle repeats 440 times each second.

The sample rate of an audio stream is how many points to store for each one of these cycles, or is how high-fidelity this "digital snapshot" of the wave is. Lots of applications use a 44.1KHz sample rate - a bit higher than 10KHz like the example. According to the sampling theorem, the threshold for ensuring you've captured a sufficient sample from an analog signal is that the sample rate must be greater than twice the frequency you you're sampling. Humans can hear about 20Hz to 20,000Hz. This means we need at least 40,000 samples, and 44,100 exceeds that. The rodio crate defaults to 48KHz, which per that same link is the standard for professional digital audio equipment.

The maximum amplitude this struct can represent is the maximum wave that fits in whatever type is used for the sample, because that's the biggest x will ever be in either direction - 1 or -1. This code uses an f32, or single-precision 4-byte float.

The rodio crate actually has a built-in rodio::source::SineWave that takes a frequency in Hertz but as an unsigned integer. Go ahead and throw a quick conversion in for our Pitch type:

// lib.rs

use rodio::source::SineWave;

impl From<Pitch> for f64 {

fn from(p: Pitch) -> Self {

p.0.into()

}

}

impl From<Pitch> for SineWave {

fn from(p: Pitch) -> Self {

SineWave::new(f64::from(p) as u32)

}

}

This code should produce an A440 tone when executed with cargo run:

// bin/music.rs

use rodio::{Sink, source::SineWave, default_output_device};

fn main() {

let device = default_output_device().unwrap();

let sink = Sink::new(&device);

let source = SineWave::from(Pitch::default());

sink.append(source);

sink.sleep_until_end();

}

I'll briefly cover the other tidbits: default_output_device() attempts to find the running system's currently configured default audio device, and a Sink is an abstraction for handling multiple sounds. It works like an audio track. You can append() a new Source of sound, and the first one appended starts the track. A newly appended track will play after whatever is playing finishes, but a rodio::source::SineWive is an infinite source.

Finally, we have to sleep_until_end() the thread until the sound completes playing (which for SineWave is never), or else the program will move right along and exit. You'll have to kill this run with Ctrl-C, this sound will play forever.

By simply modulating the pitch passed to SineWave, we could generate any pitch we want. That's what the one-liner does, it's selecting an offset to pass from the list [0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12], so we know that sequence works. And, like, cool, I guess. We can do a lot better, though. What's so special about these numbers?

A Little Music Theory

While it's great to have a voice we can sing with with, I'm sure we'd all prefer it if our program learned how to sing on key. To get oriented, A440 is the A above Middle C on a piano:

Scientific Pitch Notation

Instead of frequencies in Hertz, it's much easier to manipulate pitches in terms of Scientific Pitch Notation, another fancy name for a simple concept. The piano keyboard above was labelled according to this standard. The A440 pitch is denoted "A4" in this system. We're going to want to parse them from strings:

#[test]

fn test_new_piano_key() {

use Accidental::*;

use NoteLetter::*;

assert_eq!(

PianoKey::default(),

PianoKey {

note: Note {

letter: C,

accidental: None

},

octave: 0

}

);

assert_eq!(

PianoKey::new("A4").unwrap(),

PianoKey {

note: Note {

letter: A,

accidental: None

},

octave: 4

}

);

assert_eq!(

PianoKey::new("G♭2").unwrap(),

PianoKey {

note: Note {

letter: G,

accidental: Some(Flat)

},

octave: 2

}

);

assert_eq!(

PianoKey::new("Gb2").unwrap(),

PianoKey {

note: Note {

letter: G,

accidental: Some(Flat)

},

octave: 2

}

);

assert_eq!(

PianoKey::new("F#8").unwrap(),

PianoKey {

note: Note {

letter: F,

accidental: Some(Sharp)

},

octave: 8

}

);

}

We also want to reject invalid letters - we can use #[should_panic] to indicate that a panic is the expected behavior. No need to bother defining a real match:

#[test]

#[should_panic]

fn test_reject_piano_key_too_high() {

assert_eq!(PianoKey::new("A9").unwrap(), PianoKey::default());

}

#[test]

#[should_panic]

fn test_reject_piano_key_invalid_letter() {

assert_eq!(PianoKey::new("Q7").unwrap(), PianoKey::default());

}

Additionally, we want to go the other way. We need a to_string() or some such:

#[test]

fn test_piano_key_to_str() {

assert_eq!(PianoKey::default().to_string(), "C0".to_string());

assert_eq!(PianoKey::new("A#4").unwrap().to_string(), "A#4".to_string());

assert_eq!(PianoKey::new("Bb5").unwrap().to_string(), "B♭5".to_string())

}

A more robust system would also accept multiple accidentals and coerce, e.g. E# -> F, but this gets us going.

To implement this, it's easiest to start at the bottom. With NoteLetter, we also want to assign a numeric index but it's not as simple as with the intervals - these don't all have the same value. We will store an index:

use std::io;

use std::str::FromStr;

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

enum NoteLetter {

C = 0,

D,

E,

F,

G,

A,

B,

}

impl Default for NoteLetter {

fn default() -> Self {

NoteLetter::C

}

}

impl FromStr for NoteLetter {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

match s.to_uppercase().as_str() {

"A" => Ok(NoteLetter::A),

"B" => Ok(NoteLetter::B),

"C" => Ok(NoteLetter::C),

"D" => Ok(NoteLetter::D),

"E" => Ok(NoteLetter::E),

"F" => Ok(NoteLetter::F),

"G" => Ok(NoteLetter::G),

_ => Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is not a valid note", s),

)),

}

}

}

The notes are C-indexed, for better or for worse, so NoteLetter::default() should return that variant. We'll talk more about why it's C and not A after learning about Modes below. Don't worry, it's suitably disappointing.

Next up we have a Note which consists of a letter and optionally an accidental:

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct Note {

accidental: Option<Accidental>,

letter: NoteLetter,

}

For this one, we only want to display a character for an accidental if there's anything there:

impl fmt::Display for Note {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

let acc_str = if let Some(a) = self.accidental {

format!("{}", a)

} else {

"".to_string()

};

write!(f, "{:?}{}", self.letter, acc_str)

}

}

There's a little more logic to pull them out of strings:

impl FromStr for Note {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

let char_strs = char_strs(s);

let mut char_strs = char_strs.iter();

// note will be first

if let Some(letter) = char_strs.next() {

let letter = NoteLetter::from_str(letter)?;

if let Some(accidental) = char_strs.next() {

// check if it's valid

let accidental = Accidental::from_str(accidental)?;

return Ok(Self {

letter,

accidental: Some(accidental),

});

} else {

return Ok(Self {

letter,

accidental: None,

});

}

}

Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is not a valid note", s),

))

}

}

This uses one helper function I defined:

#[test]

fn test_char_strs() {

assert_eq!(char_strs("Hello"), ["H", "e", "l", "l", "o"])

}

If anyone has a cleaner solution I'm all ears:

fn char_strs<'a>(s: &'a str) -> Vec<&'a str> {

s.split("")

.skip(1)

.take_while(|c| *c != "")

.collect::<Vec<&str>>()

}

The missing piece is the Accidental. Accidentals are represented in strings as ♭ for flat or # for sharp, which lower or raise the note by one semitone (or Interval::Min2) respectively. This does produce 14 possible values for 12 possible semitones - the exceptions are wherever there's no black key in between two white keys.

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

enum Accidental {

Flat,

Sharp,

}

impl fmt::Display for Accidental {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

use Accidental::*;

let acc_str = match self {

Flat => "♭",

Sharp => "#",

};

write!(f, "{}", acc_str)

}

}

impl FromStr for Accidental {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

match s {

"b" | "♭" => Ok(Accidental::Flat),

"#" => Ok(Accidental::Sharp),

_ => Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is not a valid accidental", s),

)),

}

}

}

There is third accidental called "natural", ♮, which cancels these out. To represent a pitch in data we don't need it - we can get each of the piano keys with just Accidental::Sharp. We really just include Accidental::Flat for a smooth user experience - people expect those to be valid notes, even though they represent the same pitch. The natural symbol is generally used for overriding a key signature, which defines the default accidental for all the notes within a scale on sheet music. There are a series of accidentals on the margin of the staff that apply to all notes, which is how we ensure we play notes within a single given scale, or key. However, you may choose to compose a melody that contains a note outside this key. If encounter the note F#♮ on your sheet, you play an F. This program isn't (yet) smart enough to work with these.

Now we can finally define a specific tone on a full piano. A standard pitch, in our program a PianoKey, is composed of two components: a Note and a 0-indexed octave:

#[derive(Default, Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct PianoKey {

note: Note,

octave: u8,

}

To show them, we just want to print them out next to each other:

impl fmt::Display for PianoKey {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "{}{}", self.note, self.octave)

}

}

This one also has a little more logic to pull out of a string, building from the constituent components:

impl FromStr for PianoKey {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

// It makes sense to get the letter to Intervals

if let Some(octave) = char_strs(s).last() {

if let Ok(octave) = octave.parse::<u8>() {

let note = Note::from_str(&s[0..s.len() - 1])?;

if octave <= Self::max_octave() {

Ok(Self { note, octave })

} else {

Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is too high!", octave),

))

}

} else {

Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is too high for this keyboard", octave),

))

}

} else {

Err(io::Error::new(

io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput,

format!("{} is not a valid note", s),

))

}

}

}

The octave just starts at 0 and won't ever realistically rise above 255, so a u8 is fine. We can give ourselves a few convenience methods:

impl PianoKey {

pub fn new(s: &str) -> Result<Self, io::Error> {

Self::from_str(s)

}

fn max_octave() -> u8 {

8

}

}

Thanks to all the nested Default blocks, the Default implementation that the compiler derives for PianoKey corresponds to the official base pitch of this system, C0, specified in the first assertion of the test. Speaking of which, test_new_pitch() should now pass.

Intervals

The cyan key is Middle C, and A440 is highlighted in yellow. The octaves on an 88-key piano are numbered as shown, so often A440 is simply denoted "A4" especially when dealing with a keyboard. You may own a tuner that marks 440Hz/A4 specifically if you're a musician. This pitch is used for calibrating musical instruments and tuning a group, as well as a baseline constant for calculating frequencies.

Note how each octave starts at C, not A, so A4 is actually higher in pitch than C4. Octaves are "C-indexed" and base 8: C D E F G A B C is the base unmodified scale.

The smallest of interval between notes on a piano (and most of Western music) is called a semitone, also called a minor second or half step. We'll need to keep track of these as the basic unit of a keyboard interval:

#[derive(Debug, Default, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct Semitones(i8);

impl From<i8> for Semitones {

fn from(i: i8) -> Self {

Self(i)

}

}

impl From<Semitones> for i8 {

fn from(s: Semitones) -> Self {

s.0

}

}

Take a look back at that piano diagram above - one semitone is the distance between two adjacent keys. A whole step, or a major second, is equal to two semitones, or two adjacent white keys that pass over a black key. To play from C4 to C5, you'll use 12 keys (count all the white and black keys in a bracket), so octaves are divided into 12 equal semitones. There's a name for each interval:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, PartialOrd)]

pub enum Interval {

Unison = 0,

Min2,

Maj2,

Min3,

Maj3,

Perfect4,

Tritone,

Perfect5,

Min6,

Maj6,

Min7,

Maj7,

Octave,

}

By including a numeric index with Unison = 0, each variant also gets assigned the next successive ID. This way we can refer to each by name but also get an integer corresponding to the number of semitones when needed: Interval::Maj2 as i8 returns 2_i8.

Two identical notes are called a unison, with 0 cents. These intervals are defined within a single octave, so any of them apply across octaves as well - A4 and A5 are in unison just like A4 and another A4, and C4 and A5 is still a major sixth. The terms "major", "minor", and "perfect" are not arbitrary, but that discussion is outside the scope of this post. I will note that the tritone, representing 3 whole tones or 6 semitones like F-B, is the only one that's none of the three.

If interested, I recommend harmony for your next rabbit hole. The tritone takes a leading role in dissonance, and to hear it in action you should check out what the Locrian mode we defined sounds like with this program. The C major scale has a perfect fifth, 5 semitones at the dominant scale degree - and the Locrian mode has a tritone which is one extra semitone.

These all map to numbers, but we don't want to have to think about the rules when adding and subtracting. Let's do a little plumbing:

#[test]

fn test_add_interval() {

use Interval::*;

assert_eq!(Unison + Unison, Unison);

assert_eq!(Unison + Maj3, Maj3);

assert_eq!(Maj2 + Min3, Perfect4);

assert_eq!(Octave + Octave, Unison);

assert_eq!(Tritone + Tritone, Unison);

assert_eq!(Maj7 + Min3, Maj2);

}

#[test]

fn test_sub_interval() {

use Interval::*;

assert_eq!(Unison - Unison, Unison);

assert_eq!(Unison - Maj3, Min6);

assert_eq!(Maj2 - Min3, Maj7);

assert_eq!(Octave - Octave, Unison);

assert_eq!(Tritone - Tritone, Unison);

assert_eq!(Maj7 - Min3, Min6);

}

First, a little plumbing:

impl From<Interval> for i8 {

fn from(i: Interval) -> Self {

Semitones::from(i).into()

}

}

impl From<Semitones> for Interval {

fn from(s: Semitones) -> Self {

use Interval::*;

let int_semitones = i8::from(s);

match int_semitones {

0 => Unison,

1 => Min2,

2 => Maj2,

3 => Min3,

4 => Maj3,

5 => Perfect4,

6 => Tritone,

7 => Perfect5,

8 => Min6,

9 => Maj6,

10 => Min7,

11 => Maj7,

12 | _ => Interval::from(Semitones(int_semitones % Octave as i8)),

}

}

}

impl From<Interval> for Semitones {

fn from(i: Interval) -> Self {

Semitones(i as i8)

}

}

Now we can define Add and Sub:

use std::ops::{Add, Sub};

impl Add for Interval {

type Output = Self;

fn add(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Interval::from(Semitones(

i8::from(self) + i8::from(rhs) % Interval::Octave as i8,

))

}

}

impl Sub for Interval {

type Output = Self;

fn sub(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

let mut delta = i8::from(self) - i8::from(rhs);

if delta < 0 {

delta += Interval::Octave as i8;

};

Interval::from(Semitones(delta))

}

}

That gets us + and -, but we're going to want += later too and that's really easy now:

use std::ops::AddAssign;

impl AddAssign for Interval {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: Self) {

*self = *self + rhs;

}

}

We can also relate Notes to Intervals pretty well:

#[test]

fn test_get_note_interval_from_c() {

use Interval::*;

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("A").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Maj6);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("A#").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Min7);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("Bb").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Min7);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("B").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Maj7);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("C").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Unison);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("C#").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Min2);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("D").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Maj2);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("D#").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Min3);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("E").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Maj3);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("F").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Perfect4);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("F#").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Tritone);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("G").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Perfect5);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("G#").unwrap().interval_from_c(), Min6);

}

#[test]

fn test_get_note_offset() {

use Interval::*;

let a = Note::from_str("A").unwrap();

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("A").unwrap().get_offset(a), Unison);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("A#").unwrap().get_offset(a), Min2);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("B").unwrap().get_offset(a), Maj2);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("C").unwrap().get_offset(a), Min3);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("C#").unwrap().get_offset(a), Maj3);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("D").unwrap().get_offset(a), Perfect4);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("D#").unwrap().get_offset(a), Tritone);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("E").unwrap().get_offset(a), Perfect5);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("F").unwrap().get_offset(a), Min6);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("F#").unwrap().get_offset(a), Maj6);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("G").unwrap().get_offset(a), Min7);

assert_eq!(Note::from_str("G#").unwrap().get_offset(a), Maj7);

}

#[test]

fn test_add_interval_to_note() {

use Interval::*;

let a = Note::from_str("A").unwrap();

assert_eq!(a + Unison, a);

assert_eq!(a + Min2, Note::from_str("A#").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Maj2, Note::from_str("B").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Min3, Note::from_str("C").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Maj3, Note::from_str("C#").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Perfect4, Note::from_str("D").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Tritone, Note::from_str("D#").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Perfect5, Note::from_str("E").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Min6, Note::from_str("F").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Maj6, Note::from_str("F#").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Min7, Note::from_str("G").unwrap());

assert_eq!(a + Maj7, Note::from_str("G#").unwrap());

}

This all works with the logic we've already modelled:

impl From<Interval> for Note {

// Take an interval from C

fn from(i: Interval) -> Self {

use Interval::*;

let mut offset = Unison;

// That's a series of Min2

let scale = Scale::Chromatic.get_intervals();

scale.iter().take(i as usize).for_each(|i| offset += *i);

Note::default() + offset

}

}

impl Add<Interval> for Note {

type Output = Self;

fn add(self, rhs: Interval) -> Self {

let semitones = Semitones::from(rhs);

let mut ret = self;

for _ in 0..i8::from(semitones) {

ret.inc();

}

ret

}

}

impl AddAssign<Interval> for Note {

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: Interval) {

*self = *self + rhs;

}

}

For Add<Interval> for Note to work, we need to add some extra helper methods:

impl NoteLetter {

// ..

fn inc(self) -> Self {

use NoteLetter::*;

match self {

C => D,

D => E,

E => F,

F => G,

G => A,

A => B,

B => C,

}

}

}

impl Note {

fn interval_from_c(self) -> Interval {

use Accidental::*;

let ret = self.letter.interval_from_c();

if let Some(acc) = self.accidental {

match acc {

Flat => return Interval::from(Semitones::from(i8::from(Semitones::from(ret)) - 1)),

Sharp => return ret + Interval::Min2,

}

};

ret

}

fn get_offset_from_interval(self, other: Interval) -> Interval {

let self_interval_from_c = self.interval_from_c();

self_interval_from_c - other

}

fn get_offset(self, other: Self) -> Interval {

let self_interval_from_c = self.interval_from_c();

let other_interval_from_c = other.interval_from_c();

self_interval_from_c - other_interval_from_c

}

fn inc(&mut self) {

use Accidental::*;

use NoteLetter::*;

if let Some(acc) = self.accidental {

self.accidental = None;

match acc {

Sharp => {

self.letter = self.letter.inc();

}

Flat => {}

}

} else {

// check for special cases

if self.letter == B || self.letter == E {

self.letter = self.letter.inc();

} else {

self.accidental = Some(Sharp);

}

}

}

}

Hold on, though - this won't compile yet. The impl From<Interval> for Note block depends on the intervals for Scale::Chromatic, and we haven't talked about scales yet.

Scales

A scale is a series of notes (frequencies) defined in terms of successive intervals from a base note. We'll start with the major scale:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum Scale {

Major,

}

impl Default for Scale {

fn default() -> Self {

Scale::Major

}

}

Clearly, there isn't a black key between every white key - there must be a method to the madness. The piano is designed to play notes from a category of scales called diatonic scales, where the full range of an octave consists of five whole steps and two half steps. That's why our NoteLetter indices needed some extra logic - while each pair of adjacent keys is one semitone, that doesn't always mean a white key to a black key or vice versa - the note pairs B/C and E/F are both only separated by one semitone.

We can see this visually on the keyboard - it has the same 8-length whole/half step pattern all the way through. The distribution pattern begins on C, but the keyboard itself starts at A0 and ends at C8. A piano is thus designed because it can play music across the full range of diatonic scales. This is where we get those base 8 sequences - just start on a different note.

That base pattern is the C major scale. Start at Middle C, the one highlighted in cyan above, and count up to the next C key, eight white keys to the left. Each time you skip a black key is a whole step and if the two white keys are adjacent it's a half step. These are the steps you get counting up to the next C, when the pattern repeats. This totals 12 semitones per octave:

whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half

2 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1 = 12

C D E F G A B C

We can hardcode this sequence in Rust as a Vec<Interval>:

impl Scale {

fn get_intervals(self) -> Vec<Interval> {

use Interval::*;

use Scale::*;

match self {

Major => vec![Maj2, Maj2, Min2, Maj2, Maj2, Maj2, Min2],

}

}

}

We need a method to map to exact intervals:

#[test]

fn test_note_letter_to_interval() {

use Interval::*;

use NoteLetter::*;

assert_eq!(C.interval_from_c(), Unison);

assert_eq!(D.interval_from_c(), Maj2);

assert_eq!(E.interval_from_c(), Maj3);

assert_eq!(F.interval_from_c(), Perfect4);

assert_eq!(G.interval_from_c(), Perfect5);

assert_eq!(A.interval_from_c(), Maj6);

assert_eq!(B.interval_from_c(), Maj7);

}

Check out that interval sequence - we've seen something like this somewhere before:

split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,",");

Aha! It's was a major scale over one octave this whole time, as a series of semitone offsets:

whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half

2 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1

0 2 4 5 7 9 11 12

Un. Min2 Maj2 Perf4 Perf5 Maj6 Maj7 Octave

A4 B4 C#5 D5 E5 F#5 G#5 A5

Luckily we already told Rust about this when we defined the major scale. Now our modelling efforts are finally beginning to pay off:

impl NoteLetter {

fn interval_from_c(self) -> Interval {

use Interval::Unison;

Scale::default()

.get_intervals()

.iter()

.take(self as usize)

.fold(Unison, |acc, i| acc + *i)

}

}

We can work with scales using the Rust iterator methods! This function takes the first n intervals of a scale, and then uses the special impl Add for Interval logic we defined to total everything up. For instance, to calculate F, this function grabs the first 3 intervals, [Maj2, Maj2, Min2], and then sums them up, using Unison, or 0, as the base. This calculates the sum of [2,2,1], which is 5 semitones, or Interval::Perfect4.

Doing the same exercise with the same intervals starting on a different while key will also produce a major scale but you will start using the black keys to do so. C is the note that allows you to stick to only white keys with this interval pattern, or has no sharps or flats in the key signature. Before we start generating sequences of notes, though, we need a way to represent a note.

Key

For context, once again here's the original line we're dealing with:

split("0,2,4,5,7,9,11,12",a,",");

We've now discovered that that list represents the list of semitone offsets from A4 that represent an A major scale. The random notes that get produced will all be frequencies that correspond to these offsets from 440Hz.

We way, way overshot this in the process of modelling the domain. We can now automatically generate sequences of PianoKey structs that correspond to keys on an 88-key piano to select from: [C4 D4 E4 F4 G4 A5 B5 C5]. If we want a different scale, we can just ask.

We don't necessarily want to stick within a single octave, though. We want to make available the full 108 keys from C0 to B8 (even larger than the standard piano from the diagram), letting the user decide how many octaves to pick from, but only use notes in the key.

#[derive(Debug, Default, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct Key {

base_note: PianoKey,

octaves: u8,

scale: Scale,

}

impl Key {

pub fn new(scale: Scale, base_note: PianoKey, octaves: u8) -> Self {

let octaves = if base_note.octave + octaves > 8 {

PianoKey::max_octave() - base_note.octave

} else {

octaves

};

Self {

base_note,

octaves,

scale,

}

}

fn all_keys(self) -> Vec<PianoKey> {

let notes = self.get_notes();

let mut ret = Vec::new();

for i in 0..self.octaves {

notes.iter().for_each(|n| {

ret.push(

PianoKey::from_str(&format!("{}{}", *n, i + self.base_note.octave)).unwrap_or_else(|_|

PianoKey::from_str(&format!("{}{}", *n, PianoKey::max_octave())).unwrap(),

),

)

});

}

ret

}

}

These will be displayed as simply the octave-less notes in the scale:

#[test]

fn test_c_major() {

assert_eq!(

&Key::new(Scale::default(), PianoKey::default(), 1).to_string(),

"[ C D E F G A B C ]"

)

}

#[test]

fn test_a_major() {

assert_eq!(

&Key::new(Scale::default(), PianoKey::from_str("A4").unwrap(), 1).to_string(),

"[ A B C# D E F# G# A ]"

)

}

#[test]

fn test_g_major() {

assert_eq!(

&Key::new(Scale::default(), PianoKey::from_str("G4").unwrap(), 1).to_string(),

"[ G A B C D E F# G ]"

)

}

To produce all the notes in a given key, we need to calculate them from the scale and the base note:

impl Key {

// ..

pub fn get_notes(self) -> Vec<Note> {

let mut ret = vec![self.base_note.note];

let mut offset = Interval::Unison;

self.scale.get_intervals().iter().for_each(|i| {

offset += *i;

ret.push(self.base_note.note + offset)

});

ret

}

}

impl fmt::Display for Key {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

let notes = self.get_notes();

let mut ret = String::from("[ ");

notes.iter().for_each(|n| ret.push_str(&format!("{} ", *n)));

ret.push_str("]");

write!(f, "{}", ret)

}

}

This uses the impl Add for Interval logic we'd previous defined to count up successive intervals across a scale, resulting in a more concrete set of notes. Now we can add the Display implementation used in the test code - this trait also provides the to_string() method:

impl fmt::Display for Key {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

let notes = self.get_notes();

let mut ret = String::from("[ ");

notes.iter().for_each(|n| ret.push_str(&n.to_string()));

ret.push_str("]");

write!(f, "{}", ret)

}

}

Circle of Fifths

With Key defined, we can start talking about other scales.

Using the same intervals as the C major scale starting on a different note will also produce a major scale but you will start using the black keys. This is called the key signature, and there's one for each variant of the major scale starting from each black key. They're related by the circle of fifths:

The C major scale has all white keys. To find the version of the major scale that adds one single black key to augment a tone, you go up a perfect fifth, or 7 semitones: Interval::Perfect5. This has a ratio 3:2.

One perfect fifth up from C is G, so the next scale around the circle is G major. It has one sharp: A. Go back up to the piano diagram and count up the major scale sequence from G, for example one note below the yellow A4. You'll need the F# black key at the last step right before G5, but all the other hops white stick to the white keys. D major will need two black keys, F# and C#. If you continue incrementing a fifth (remember, octave is irrelevant here), you'll hit all 12 possible patterns before getting back to C. To get through all the key signatures incrementally, one accidental at a time, you keep going up by perfect fifths. Once you come all the way back to C, you'll have hit all 12 keys, encompassing all possible key signatures.

This diagram also shows the relative natural minor for each. That's a sneak preview of the Aeolian mode in the next section!

It's true that, e.g. D# and E♭ represent the same pitch - what's different is why we got there. After the midway point, it's easier to denote 5 flats than 7 sharps, even though they mean the same tones - there's only 5 black keys to choose from, after all.

To go counter-clockwise, go up by a perfect fourth every time, which is 5 semitones. This is known as "circle of fourths", and is more commonly associated with jazz music whereas fifths are seen in more classical contexts.

This program doens't use it, but we can generate all of them by just passing each note into Key::new():

impl Scale {

pub fn circle_of_fifths() -> Vec<Key> {

let mut ret = Vec::new();

// Start with C

let mut current_base = Note::default();

// Increment by fifths and push to vector

for _ in 0..ScaleLength::Dodecatonic as usize {

ret.push(Key::new(Scale::default(), ¤t_base.to_string()));

current_base += Interval::Perfect5;

}

ret

}

}

That's twelve scales for free:

[ C D E F G A B C ]

[ G A B C D E F# G ]

[ D E F# G A B C# D ]

[ A B C# D E F# G# A ]

[ E F# G# A B C# D# E ]

[ B C# D# E F# G# A# B ]

[ F# G# A# B C# D# F F# ]

[ C# D# F F# G# A# C C# ]

[ G# A# C C# D# F G G# ]

[ D# F G G# A# C D D# ]

[ A# C D D# F G A A# ]

[ F G A A# C D E F ]

This implementation isn't smart enough to switch to flats halfway through to represent the black keys used - could be a fun mini-challenge! Maybe you could extend this to hop to different scales around the circle periodically.

Diatonic Modes

Now we can produce the 12 transpositions of major scale from C - just pick any note of the keyboard and count up the same intervals. However, this pattern of white and black repeats all the way up and down the whole length of the keyboard - what if we didn't start at C to set the base of the black-key/white-key pattern? Why not use A B C D E F G A?

If you start on any other white key and count up one octave skipping all the black keys, you will get a different diatonic scale than a major scale. These scale variations are called Modes, and while high-school me was terrified of and terrible at whipping out arbitrary ones on a brass instrument from memory (mental math is not one of my talents), they're easy to work with programmatically (and much less stressful).

The major scale is also known as the Ionian mode. This is the base mode, each other is some offset from this scale. As we've seen, the key you need to start on to play this mode with no black keys (accidentals) is C.

The natural minor scale, is obtained by starting at A4 and counted up white keys, is called the Aeolian mode. Try it yourself on the diagram - march on up the white keys from A4 to A5:

whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole

This should look like the C major scale, no sharps or flats, but with A at the beginning:

#[test]

fn test_a_minor() {

use Mode::*;

use Scale::*;

assert_eq!(

&Key::new(Diatonic(Aeolian), PianoKey::from_str("A4").unwrap(), 1).to_string(),

"[ A B C D E F G A ]"

)

}

It's the same pattern, just starting at a different offset. You can play a corresponding minor scale using only the white keys by simply starting at the sixth note of the C major scale (or incrementing a major sixth), which is A. Try counting it out yourself up from A4.

There's an absurdly fancy name for each offset:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq, PartialOrd)]

pub enum Mode {

Ionian = 0,

Dorian,

Phrygian,

Lydian,

Mixolydian,

Aeolian,

Locrian,

}

We'll hardcode the C major sequence as the base:

whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half

2 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1

impl Mode {

fn base_intervals() -> Vec<Interval> {

use Interval::*;

vec![Maj2, Maj2, Min2, Maj2, Maj2, Maj2, Min2]

}

}

Let's also hardcode the scale length:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum ScaleLength {

Heptatonic = 7,

}

Now we can make our scales a little smarter:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum Scale {

- Major,

Diatonic(Mode),

}

impl Default for Scale {

fn default() -> Self {

- Scale::Major

+ Scale::Diatonic(Mode)

}

}

impl Scale {

fn get_intervals(self) -> Vec<Interval> {

use Interval::*;

use Scale::*;

match self {

- Major => vec![Maj2, Maj2, Min2, Maj2, Maj2, Maj2, Min2],

+ Diatonic(mode) => Mode::base_intervals()

+ .iter()

+ .cycle()

+ .skip(mode as usize)

+ .take(ScaleLength::Heptatonic as usize)

+ .copied()

+ .collect::<Vec<Interval>>(),

+ }

}

}

Now we've got seven modes for each of twelve keys on the keyboard - that's 84 distinct key signatures. The Ionian and Aeolian modes have nicknames, the rest we'll just work with as the mode names:

impl FromStr for Scale {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

use Mode::*;

use Scale::*;

match s.to_uppercase().as_str() {

"IONIAN" | "MAJOR" => Ok(Diatonic(Ionian)),

"DORIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Dorian)),

"PHRYGIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Phrygian)),

"LYDIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Lydian)),

"MIXOLYDIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Mixolydian)),

"AEOLIAN" | "MINOR" => Ok(Diatonic(Aeolian)),

"LOCRIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Locrian)),

_ => Err(io::Error::new(io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput, "Unknown scale")),

}

}

}

impl fmt::Display for Scale {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

use Scale::*;

let s = match self {

Diatonic(mode) => {

use Mode::*;

match mode {

Aeolian => "minor scale".into(),

Ionian => "major scale".into(),

_ => format!("{:?} mode", mode),

}

}

};

write!(f, "{}", s)

}

}

The fact that Ionian Mode/C Major is Offset 0 is actually somewhat arbitrary - though definitely not completely. There's a reason C major is so commonly found in music - it sounds good.

I did a bare-minimum amount of research and found it's an "unfortunate historical accident". In a sentence, the concept of "mode" in an equally tempered system predates the modern scales and C == 0 is a historical artifact. The letters were originally numbered from A, of course, but got mapped to frequencies well before the modern modes we use now were honed and refined from previous systems. The system eventually came to be based around the C major scale, not A major. By then the fact that what's now Middle C was 261.626Hz was long done and over with.

Non Heptatonic Scales

Okay, Ben. Ben, okay. Okay, Ben. We've arrived at the version from the blog post, great. You also promised 86 in the introduction, not 84. This whole time, though, the line from the meme image has had something different:

split("4,5,7,11",a,",");

The diatonic scales we've been working with are a subset of the heptatonic scales, with seven notes each. These tones are naturally further apart than we've been using. Let's add a couple others scale lengths to play with:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum ScaleLength {

+ Tetratonic = 4,

Heptatonic = 7,

+ Dodecatonic = 12,

}

Interestingly, the scale shown is tetratonic, given as octave-less notes, intervals from base, and offsets from A440:

[C#, D, E, G#]

[Min2, Maj2, Maj3]

[4, 5, 7, 11]

Oddly, this scale is primarily associated with pre-historic music and not often found since. Was AWK passed down from the before-times? I also don't understand how that snippet works, because it's still indexed with a[$1 % 8], but I'm too lazy to find out why.

The only dodecatonic scale is the chromatic scale is just all the notes:

[A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#]

[Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2]

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

Who needs key signatures anyhow, that's a waste of all these other keys! This one throws 'em all in the mix.

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum Scale {

Chromatic,

// ..

}

The chromatic scale is for people who don't have time to muck about with petty concerns like sounding good, and don't want to waste any piano keys - it's just 11 successive minor 2nds, giving you every note.

half, half, half, half, half, half, half, half, half, half, half

A A# B C C# D D# E F F# G G#

Or, in Rust:

#[test]

fn test_chromatic_intervals() {

use Interval::Min2;

assert_eq!(

Scale::Chromatic.get_intervals(),

vec![Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2, Min2]

);

}

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub enum Scale {

+ Chromatic,

Diatonic(Mode),

+ Tetratonic,

}

impl Scale {

// ..

fn get_intervals(self) -> Vec<Interval> {

use Interval::*;

use Scale::*;

match self {

+ Chromatic => [Min2]

+ .iter()

+ .cycle()

+ .take(ScaleLength::Dodecatonic as usize)

+ .copied()

+ .collect::<Vec<Interval>>(),

Diatonic(mode) => Mode::base_intervals()

.iter()

.cycle()

.skip(mode as usize)

.take(ScaleLength::Heptatonic as usize)

.copied()

.collect::<Vec<Interval>>(),

+ Tetratonic => vec![Min2, Maj2, Maj3],

}

}

}

impl FromStr for Scale {

type Err = io::Error;

fn from_str(s: &str) -> Result<Self, Self::Err> {

use Mode::*;

use Scale::*;

match s.to_uppercase().as_str() {

"IONIAN" | "MAJOR" => Ok(Diatonic(Ionian)),

"DORIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Dorian)),

"PHRYGIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Phrygian)),

"LYDIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Lydian)),

"MIXOLYDIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Mixolydian)),

"AEOLIAN" | "MINOR" => Ok(Diatonic(Aeolian)),

"LOCRIAN" => Ok(Diatonic(Locrian)),

+ "CHROMATIC" => Ok(Chromatic),

+ "TETRATONIC" => Ok(Tetratonic),

_ => Err(io::Error::new(io::ErrorKind::InvalidInput, "Unknown scale")),

}

}

}

impl fmt::Display for Scale {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

use Scale::*;

let s = match self {

+ Chromatic | Tetratonic => format!("{:?} scale", self).to_lowercase(),

Diatonic(mode) => {

use Mode::*;

match mode {

Aeolian => "minor scale".into(),

Ionian => "major scale".into(),

_ => format!("{:?} mode", mode),

}

}

};

write!(f, "{}", s)

}

}

This could be a potential natural application of dependent types, a programming language feature that Rust does not support. Few languages do. One example is Idris, which is like Haskell++. A dependent type codifies a type restraint that's dependent on a value of that type. The linked example describes a function that appends a list of m elements to a list n which specifies as part of the return type that the returned list has length n + m. A caller can then trust this fact implicitly, because the compiler won't build a binary if it's not true. I think this could be applied here to verify that a scale's intervals method returns an octave, regardless of length. That can be tested for in code with Rust, of course, but not encoded into the type signature directly.

Those are just two examples, I bet you could find some other interesting patterns on the keyboard diagram. For instance, what happens if you ignore the white keys and only use the black keys?

Generating Music

It's finally time to make some music. We've now built ourselves a toolkit for working with piano keys and intervals, and a separate type for dealing with a frequency in Hertz, and they both know how to interact with the same Interval variants. Now we need to get from PianoKey obtects to Pitches.

Cents

Discrete units like Semitones are useful for working with a keyboard, but as we know, sound is analog and continuous. We need to subdivide these intervals even more granularly, and because of equal temperament we're free to do so at any arbitrary level.

Beyond the twelve 12 semitones in an octave, each semitone is divided into 100 cents. This means a full octave, representing a 2:1 ratio in frequency, spans 1200 cents, and each cent can be divided without losing the ratio as well if needed:

#[derive(Debug, Default, Clone, Copy, PartialEq)]

pub struct Cents(f64);

We need to do a little plumbing to let ourselves work at this higher level of abstraction. We need to be able to translate our discrete Semitones into Cents ergonomically:

#[test]

fn test_semitones_to_cents() {

assert_eq!(Cents::from(Semitones(1)), Cents(100.0));

assert_eq!(Cents::from(Semitones(12)), Cents(1200.0));

}

We can give ourselves some conversions to the inner primitive:

impl From<f64> for Cents {

fn from(f: f64) -> Self {

Cents(f)

}

}

impl From<Cents> for f64 {

fn from(c: Cents) -> Self {

c.0

}

}

Now we can encode the conversion factor:

const SEMITONE_CENTS: Cents = Cents(100.0);

impl From<Semitones> for Cents {

fn from(s: Semitones) -> Self {

Cents(i8::from(s) as f64 * f64::from(SEMITONE_CENTS))

}

}

With that in place, we're ready to start working with intervals directly and have Rust understand them in terms of cents:

#[test]

fn test_interval_to_cents() {

use Interval::*;

assert_eq!(Cents::from(Unison), Cents(0.0));

assert_eq!(Cents::from(Min2), Cents(100.0));

assert_eq!(Cents::from(Octave), Cents(1200.0));

}

We need Interval variants to map directly to Semitones instead of plain integers, to make sure they're always turned into Cents correctly:

With that, it's easy to map Intervals to Cents:

impl From<Interval> for Cents {

fn from(i: Interval) -> Self {

Semitones::from(i).into()

}

}

Phew! Lots of code, but now we can operate directly in terms of Interval variants or anything in between and everything stays contextually tagged. Verify with cargo test that everything checks out.

There's one more step to get from our brand new floating point Cents to frequencies in Hertz though. Remember how Middle C was some crazy fraction, 261.626Hz? This is because cents are a logarithmic unit, standardized around the point 440.0. While a 2:1 ratio is nice and neat, we've been subdividing that arbitrarily wherever it makes sense to us. Now the arithmetic isn't always so clean. Doubling 440.0Hz will get 880.0Hz, but how would we add a semitone?

We know that to increase by one octave we double the frequency: 440 * 2. We'd need to increase by a 12th of what doubling the number would do for a single semitone: 440 * 2^(1/12). Looks innocuous enough, but my calculator gives me 466.164, Rust gives me 466.1637615180899 - not enough to perceptually matter, but enough that it's important that the standard is the interval ratio and not the specific amount of Hertz to add or subtract. Those amounts will only be precise in floating point decimal representations at exact octaves from the base note, because that's integral factor after multiplying by 1 in either direction, 2 or 1/2.

Otherwise stated, the ratio between frequencies separated by a single cent is the 1200th root of 2, or 2^(1/1200). In decimal, it's about 1.0005777895. You wouldn't be able to hear a distinction between two tones a single cent apart. Using this math, it works out to just shy of 4 cents to cause an increase of 1Hz, more precisely around 3.9302 for a base frequency of 440.0.

Logarithmic units are helpful when the range of the y axis, in our case frequency, increases exponentially. We know the graph of frequency to pitch does because to jump by any single octave, we double what we have - we're multiplying at each step, not adding (which results in a linear graph). A4 is 440Hz, A5 is 880Hz, and by A6 we're already at 1,760Hz. The graph f(x) = x^2 looks like this:

A logarithm is the inverse of an exponent. Our ratio had an exponent that was "1 divided by n", which is the inverse of raising something to the power of "n divided by 1", such as squaring it (n=2). This is otherwise written as an "nth root", in the case of a cent n being 1,200. This counteracts the rapid growing curve we get by constantly squaring the frequency into a more linear scaled subdivision between octaves:

Notice it's not a straight diagonal. We haven't removed the fact that frequencies are being multiplied, merely adjusted for it. We're taking a logarithm of something that has been squared, the frequency. This tames the steep increase but the line is still slightly curved.

Fractional cents and tones are a much better way to deal with intervals than by concrete frequency deltas. Knowing all this we can translate back to the frequency in Hertz of a desired pitch if we know both a base frequency and the number of cents to increase by:

Here, a is the initial frequency in Hertz, b is the target frequency, and n is the number of cents by which to increase a.

Lets try to increase the standard pitch by single Hertz using the value above:

#[test]

fn test_add_cents_to_pitch() {

let mut pitch = Pitch::default();

pitch += Cents(3.9302);

assert_eq!(pitch, Pitch::new(Hertz(441.0)));

}

It looks like we're going to need to divide some Cents, leveraging the impl From<Cents> for f64 blocks we already defined:

use std::ops::Div;

impl Div for Cents {

type Output = Self;

fn div(self, rhs: Self) -> Self {

Cents(f64::from(self) / f64::from(rhs))

}

}

This is just performing floating point division on the inner value, but keeps it wrapped up in the Cents context for us so we can directly use Cents(x) / Cents(y). We now know enough to manipulate a Pitch directly.

The AddAssign trait gets us the += operator, and can define it for any type we want on the right hand side:

use std::ops::AddAssign

impl AddAssign<Cents> for Pitch {

#[allow(clippy::suspicious_op_assign_impl)] // needed to stop clippy from yelling

fn add_assign(&mut self, rhs: Cents) {