This article was originally posted on The Simple Programmer. Images and links are courtesy of their team. I got to work with a team of really amazing editors and it was a great experience. I think, overall, it helped the article come out way better than I originally imagined it. I cannot recommend working with an editor enough. You have to give up a bit of creative control on the article and put on a team mindset, but it's definitely worth it. You can write for Simple Programmer too. Just submit an article draft or idea!

Programming is hard. It’s fun, it’s rewarding, but it’s definitely not easy. In order to be successful and productive, being able to get into that deep focus state and stay there is key.

At the same time, it seems like the universe is trying its best to keep you out of that state by peppering you with other things that clamor for your attention at irregular and infuriatingly unpredictable intervals: email, meetings, phone calls, and more.

Even if you manage to successfully get rid of all of the unnecessary distractions, there is some minimum amount of outside world engagement that is required to be a successful and well-adjusted employee, co-worker, and human being. Depending on how much you’re storing “in memory” at any given time, even these small distractions can be enough for you to lose your focus and have to get back into “the zone.”

That being said, here’s the question: how do you keep track of your thoughts? How do you make sure that everything you need to do gets done?

Everybody has some sort of system—even not having a system and trying to remember everything is technically a system. I wanted to share mine because it seems to work pretty well.

There's a method that is fairly well-established called the "Getting Things Done" (GTD) approach for managing the things that you have to do. It was created by David Allen around 2002 and been discussed in Wired magazine and on Hanselminutes (Scott Hanselman’s podcast). I heard about it from Wes Bos and Scott Tolinski on their Syntax podcast. You can read more about the philosophy behind it on the Getting Things Done website.

I'll go over my own process step by step, which is loosely based on the GTD approach. I like to think about it in terms of a few catchy mantras that I came up with all by myself.

1. Remember Nothing; Record Everything.

Don't remember anything. You're not good at it. Find someplace to store all the things you need to think about and remember.

I use Trello because it’s a tool that really fits with how my brain works. Trello is a web app that provides users with any number of boards, which are basically blank canvases that will eventually house all of your to-dos, ideas, projects, and everything else.

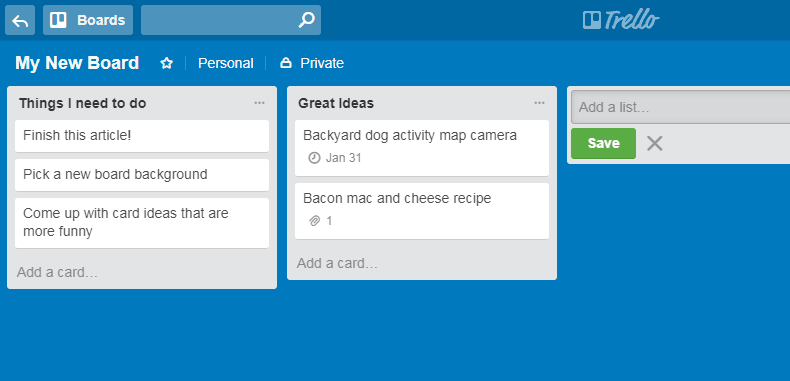

On these boards, you can create lists, which are vertically aligned and ordered collections of cards.

You can use these cards to store individual brain items. They can have images, comments, documents (like this article), checklists, and even due dates attached to them. I call this system my Other Brain.

The most important feature for me is that Trello allows you to drag and drop your lists and cards. You can create a task, keep all the information about that task (including conversations, history, and data) bundled along with the same card, and even use your lists as a form of workflow control.

For example, you might have several stages to your programming workflow: tasks that are pending, currently-being-worked-on, ready for review, and those that are finished and ready to publish/push this week. You can create a card when you first get a task and just drag it from one list to the next as you work. This process gives you a nice, visual snapshot of your progress at any given point.

If you’ve got a ton of items in the pending list and someone asks you if you have time to take on just one more quick task, there is a concrete record that you can look at, instead of trying to remember all of the things you have to do.

Personally, I tend to make lists based on the category of the thing. Is it somebody else’s blog post I want to remember to read later? Is it a future idea for my own blog? Is it a programming project to complete? I’ve got a list for that.

And as you list your tasks, try to sort your thoughts in order of urgency and/or ease of completion. I like to put the things that I need to (or can) finish first down at the bottom of my lists and work my way up.

Sorting your tasks allows you to quickly find the next thing you need to work on and get started in it, minimizing the brain space your task management system takes up.

If Trello doesn’t fit your style, use a note-taking app, an actual paper notebook, or something else. The important thing is that you get everything out of your head!

Here’s why. You’ve only got so much brain. Granted, you’re reading articles on Simple Programmer, so you’ve probably got a lot of brains. But it’s a finite amount. If you’re carrying everything you have to do later around in your head, you’re not using that space for thinking about the thing you need to do now.

For programmers especially, having that extra space can make a big impact. When you’re programming, you need to be able to simulate the code in your head, stepping through each line and understanding how that line affects the current values of each variable. This process necessarily means that you need to constantly be remembering what variable values are, what function inputs could be, and—depending on those values—which branches of program flow could be triggered.

Having the space to accommodate all of these values in your “mental memory,” without bumping up against the space containing your dentist appointment at 3:30 or what you’re going to say to the customer tomorrow morning, can make your life significantly less error-prone and stressful.

In the same way that you feel better and more productive when you clear off your desk, clean up your room when it’s messy, or refactor your code, this step is all about cleaning out your brain.

Once you’ve picked how you want to store your information, you can begin the process. The very second you:

- have a brilliant idea,

- remember something you have to do,

- finish a feature which causes you to have new problems,

- someone stops by your desk to ask you to take a look at something,

- get an email from a customer that needs a long answer,

- or get assigned something at a meeting, put it in your Other Brain.

Feel free to make your Other Brain pretty, and create various sections for different parts of your brain. I’ve got one board for personal/programming stuff, one for work (I design plastic molds), and one for house chores and to-dos that I share with my wife.

2. Your Inbox Is a Receiving Area, Not a To-Do List

After you get your Main Brain cleaned out and offloaded into your Other Brain, you need to stop all of the junk that’s pouring into your Main Brain from cluttering it up. The main place this junk pours in, especially in the professional setting, is your email inbox.

For me, I do a lot of customer-facing work: generating quotes, formalizing requirements, and working through design issues with customers. For you, maybe it’s tons of QA tickets or new issues being filed. Maybe you’ve got several different projects and chat notifications coming in from different sources.

I used to keep things in my email inbox until I was done with them. Then I realized that having a full inbox stresses me out. It makes me feel like I have a billion things to do, and there's no categorizing or organization. It's just a big 💩-pile of things that make me feel bad and give me anxiety.

Now, a couple of times a day, I open up my email. For each thing, if I can handle it quickly, I take care of it right away.

The question that goes through my head is, “Can I answer this in the next 30 seconds, without stopping and looking something up?” And depending on how overwhelmed I’m feeling by things that aren’t yet tracked in my Other Brain, that time limit gets shorter and shorter.

If it's going to take me a little while to track down the answer or information I need to respond, I enter it into my Other Brain and archive it in its corresponding email folder. When in doubt, put it in the Other Brain.

One way or another, it's out of my inbox quickly and painlessly. Generally, this lets me get to Inbox Zero in less than an hour. (Hopefully).

3. Get Things Done, One Bite at a Time

After you've stemmed the tide of ideas, emails, and people asking you to do things, open up your Other Brain and get to work. Don't get freaked out by everything that's on your list, because it will probably be a lot. It's your whole Other Brain!

But since you don't have to spend valuable time remembering all the things you have to do, you're going to be able to fully focus on your tasks. And since you've already pre-sorted your thoughts by order of importance, you should be able to look at your list and find the first thing that needs to be done.

Do it. Don't think about any of the other things. Once you're done, cross it off, archive it, or do whatever you have to do to close it out. And find the next thing. Do it again and again until you are tired, hungry, or your list is empty.

The nice thing about this approach is that it matters less if you get interrupted or if somebody jams something in the front of your queue in a panic. It allows you to stay in that all-important deep-focus state, since the act of putting something in your Other Brain doesn’t take nearly as much focus as actually handling the item that threatens to disrupt your concentration. You just file the interruption into the Other Brain, and when they go away, you get right back into your tasks!

Now, Get Started Getting Things Done

That's it. Remember nothing, get everything out of your brain and your inbox, record everything somewhere, and do the things you can, when you can focus, one bite at a time.

I no longer spend entire days trying to get all the way through my inbox. I forget which methods to write next way less frequently. My ideas for projects and posts like this one are no longer just shower thoughts that disappear after fifteen minutes.

When you’re coding, in order to know what you’re program is doing, you have to be the computer—and that takes a lot of focus.

Like, “everything you’ve got” levels of focus.

Like, “if someone asks you a question in the middle of a session, you have to stare blearily at them for a second, figure out who they are and what’s happening, and probably end up saying ‘Um. What?’” levels of focus.

So, distracting yourself with anything else while you’re doing that is not only unproductive—it’s unnecessary. I mean, come on! We’re programmers. We’ve got tools for this. Automate it, delegate it, and get back to the fun stuff.