For more content like this subscribe to the ShiftMag newsletter.

“No vulnerability, no creativity. No tolerance for failure, no innovation. It is that simple. If you’re not willing to fail, you can’t innovate. If you’re not willing to build a vulnerable culture, you can’t create.”

— Brene Brown, professor and author

I believe there to be two types of people in the workplace:

- those who strongly believe being vulnerable at work is a sign of weakness that will be used against them,

- and those who have had that happen but still do it to stay authentic, hoping it will pay off in the long run.

I’ve spent years working with both types. I’ve also worked in other people’s teams, as well as built my own. In this article, we will discuss why a detached engineer only sabotages the team, the company, and the individual and how vulnerability can have an incredible impact if used correctly.

Me against the world mentality

In the current job market, where an average software engineer stays just 2 years at a single company, where remote work and freelancing lead to engineers having 2 or 3 full-time positions at the same time, and companies are firing thousands of software engineers with little to no notice, it’s easy to adopt me against the world mentality.

This way of thinking leads us to always compete with everyone else for superiority, material prosperity, and recognition. Pushing it further, it reduces any chance for real, meaningful connections and can instill paranoia. Shutting everyone out gives us a false sense of security, as no one can really hurt us (or at least they won’t know they did.)

When I first started working, I was overwhelmed with the feeling of incompetence. Surrounded by brilliant engineers who talked in terms I didn’t understand, the adaptation was hard. Every time I had to ask for help or when something didn’t work, I felt shame. To cope with it, I followed my instincts and emotionally shut out, trying not to feel overcome by agitation and shame.

Two years in, this was still my main coping mechanism. Whenever frustrations with myself or my colleagues would arise, I’d try to ignore it and just move on because that way no one could judge me for my weaknesses and shortcomings.

Looking back at my 10 years of professional development, the single greatest impact on it was accepting my emotions, my limitations in knowledge and capabilities, and being open about them.

A wake-up call came from someone dear to me, who was, in many ways, my mentor. They helped me realize that I was bottling up emotions – a situation that’s neither sustainable nor optimal. After that, it was up to me: would I adapt my instinct reactions and start showing real vulnerability?

I believe I’ve made the right choice. To this day, it helps me stay authentic and honest, gives power to my words, and helps me connect with people more easily.

Showing vulnerability in a team

Great software companies don’t measure productivity and output at an individual level but at the team level. This not only incentivizes everyone to work together but also disrupts the me against the world mentality.

A lot of the successful teams’ dynamics come down to trust. Trust between team members is the glue that holds everything together when things get hard. Everyone has good and bad days — sometimes that means things don’t get communicated correctly or at all. Working closely with someone means there will be a million opportunities to be disappointed or frustrated.

In these times, we need to trust that someone doesn’t mean us harm, giving them the benefit of the doubt and being honest if things aren’t working out. If the trust is mutual and the goals are aligned, it will be a net-positive game.

Great teams don’t have perfect members. Instead, they have honest, open communication that nurtures trust and a feeling of unity.

I’ve been a part of both toxic and nurturing teams, and the dynamics are completely different. Toxicity disrupts everything, from communication to cooperation and delivery speed. Something I’ve learned over the years is – when faced with toxic team members, their attitudes and behavior need to be addressed directly, no matter their brilliance and output. Otherwise, their negative influence will pull everyone down and affect the team spirit.

The first step in addressing such situations is direct and honest communication, expressing our observations and feelings. I believe people are inherently good, and toxicity comes from unaddressed issues in the past coupled with some personal insecurities. Although the past can’t be changed, together, we can commit to doing better in the future.

WholeHearted School Counseling

Talking in private with a person about the negative feelings they might be causing is incredibly hard. The first time I organized such a conversation was with a senior peer, and it was one of the scariest things I ever did in my career. It was long, intense and honest. We were both open, constructive, and non-judgmental. By the end, I had massive newly-found respect for my colleague, even though things didn’t work out in the long run.

If we can find that common language with such individuals, the focus switches from “addressing toxicity” to “mending relationships,” which is a much more constructive outlook. If we then successfully continue to improve that relationship, things will start to heal, and trust will slowly be re-established! If it goes the other way, at least we gave it our best.

Champions of vulnerability

An environment that cherishes vulnerability also encourages authenticity and gives employees a feeling that they can speak up and make suggestions, agree and disagree, and admit mistakes. It entices learning through sharing and creating genuine connections with the team.

The first step towards creating such a culture is leading by example — not compromising on honesty and accepting the hard and uncomfortable conversations. It is also important to educate others about it, about the benefits, but also the misconceptions that showing vulnerability is a sign of weakness.

Vulnerability is something we cannot enforce, as it would have the opposite effect. It starts with a safe environment, people who care about one another, and who focus on learning over outcomes.

Working in a startup is especially challenging — the hours are long, the pay is bad compared to many other places, the documentation is lacking, and the processes are semi-defined at best. Having interviewed hundreds of candidates, I realized that the best filtering strategy is showing real vulnerability. I am very open about all these downsides and will emphasize them in interviews.

Some candidates will either be attracted by this, and will see these challenges as an opportunity to grow and make an impact. Most will say thank you, no thank you. And I’m OK with that, as it saves us all some time, regardless of the fact that we might miss some incredible engineers.

Not compromising on vulnerability is incredibly powerful and has lasting effects. I realized that during my last vacation when my team had 2 production outages. They realized there was something wrong, alerted the clients, did damage control, fixed the mistakes, and made sure something like this wouldn’t happen again — all while I was gone. From what I heard, it was extremely stressful, intense, and at times unpleasant.

During all that time, there was no shaming or finger-pointing. Everyone tackled it as a team. Furthermore, the individuals in charge of the failing systems immediately spoke up when they detected something was wrong and chose not to hide. They showed real vulnerability and courage, and everyone else rewarded them with support. This wouldn’t have happened if our sole priority was engineering excellence and not finding a cultural fit.

If we’re not in a position of high influence, we can’t really expect to change the whole company, its hiring processes, or its core principles. However, we can influence the team we work in. We can share our feelings and ideas, honestly talk about potential improvements, actively listen, and be vulnerable. We can be champions of vulnerability — role models for others to do the same.

Conclusion

There are two types of people in the workplace: those who feel alone and threatened by others and those who treat work as a net-positive game.

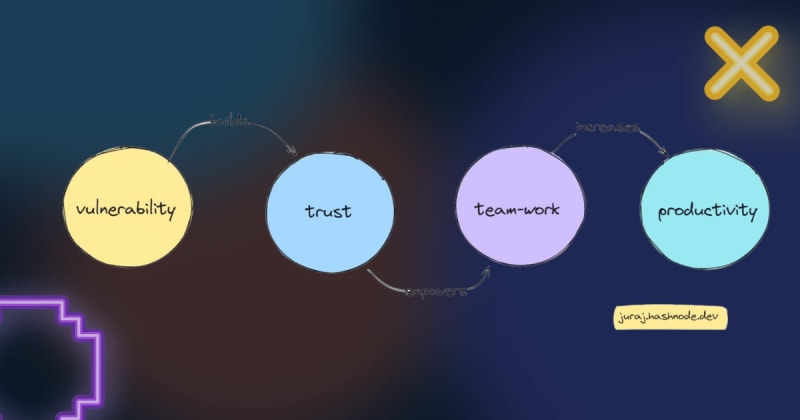

By being vulnerable with our team members, we instill trust and a sense of connection, we empathize with colleagues who struggle, doubt themselves, or feel overwhelmed. We demonstrate a strength of character and show self-awareness.

These are the foundations that build great teams. With challenges brought by remote work and a crazy job market, it is very important to prioritize what really matters, which is people.

If you’re someone in an influential position, create an environment where people will feel appreciated, included, and relied upon. And if you’re someone who’s just starting out, find a place where your potential and passion will be cherished and your failures treated as learning opportunities.

We need courage and grit to be vulnerable — that’s hard. But everyone will know us for our authentic, honest selves, which pays off in the long run.

P.S. To learn more about vulnerability, I suggest you read Daring Greatly by _Brene Brown; i_t helped me better understand things I see in my everyday life.

The post Death to the invincible engineer appeared first on ShiftMag.