There has been some buzz recently in the frontend world around the term "Signals". In seemingly short order they seem to be everywhere showing up in everything from Preact to Angular.

But they are not a new thing. Not even remotely if you consider you can trace roots back to research in the late 1960s. At its foundation is the same modeling that enabled the first electronic spreadsheets and hardware description languages (like Verilog and VHDL).

Even in JavaScript, we've had them since the dawn of declarative JavaScript Frameworks. They've carried various names over time and come in and out of popularity over the years. But here we are again, and it is a good time to give a bit more context on how and why.

Disclaimer: I am the author of SolidJS. This article reflects the evolution from the perspective of my influences. Elm Signals, Ember's computed properties, and Meteor all deserve shoutouts although not covered in the article.

Unsure what Signals are or how they work? Check out this Introduction to Fine-Grained Reactivity:

In the Beginning...

It is sometimes surprising to find that multiple parties arrive at similar solutions around exactly the same time. The starting of declarative JavaScript frameworks had 3 takes on it all released within 3 months of each other: Knockout.js (July 2010), Backbone.js (October 2010), Angular.js (October 2010).

Angular's Dirty Checking, Backbone's model-driven re-renders, and Knockout's fine-grained updates. Each was a little different but would ultimately serve as the basis for how we manage state and update the DOM today.

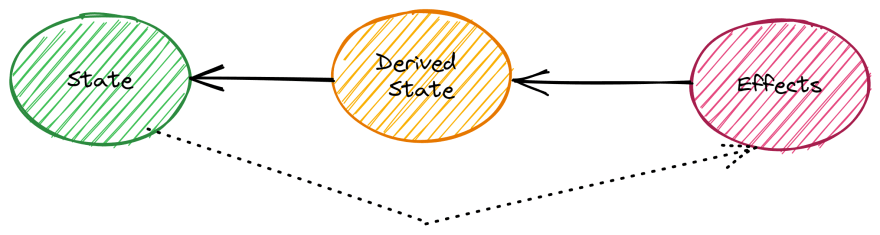

Knockout.js is of special importance to the topic of this article, as their fine-grained updates were built on what we've come to call Signals. They introduced initially 2 concepts observable (the state) and computed (side effect) but over the next couple of years would introduce the 3rd pureComputed (derived state) to the language of the frontend.

const count = ko.observable(0);

const doubleCount = ko.pureComputed(() => count() * 2);

// logs whenever doubleCount updates

ko.computed(() => console.log(doubleCount()))

The Wild West

Patterns were a mix of patterns learned from developing MVC on the server and the past few years of jQuery. One particular common one was called Data Binding which was shared both by Angular.js and Knockout.js although in slightly different ways.

Data Binding is the idea that a piece of state should be attached to a specific part of the view tree. One of the powerful things that could be done was making this bi-directional. So one could have state update the DOM and in turn, DOM events automatically update state all in an easy declarative way.

However, abusing this power ended up being a foot gun. But not knowing better we built our applications this way. In Angular without knowledge of what changes it would dirty check the whole tree and the upward propagation could cause it to happen multiple times. In Knockout it made it difficult to follow the path of change as you'd be going up and down the tree and cycles were common.

By the time React showed up with a solution, and for me personally, it was the talk by Jing Chen that cemented it, we were more than ready to jump ship.

Glitch Free

What was to follow was the mass adoption of React. Some people still preferred reactive models and since React was not very opinionated about state management, it was very possible to mix both.

Mobservable (2015, later shortened to MobX) was that solution. But more than working with React it brought something new to the table. It emphasized consistency and glitch-free propagation. That is that for any given change each part of the system would only run once and in proper order synchronously.

It did this by trading the typical push-based reactivity found in its predecessors with a push-pull hybrid system. Notification of changes are pushed out but the execution of the derived state was deferred to where it was read.

For a better understanding of Mobservable's original approach check out: Becoming Fully Reactive: An in Depth Explanation of Mobservable by Michel Westrate.

While this detail was largely overshadowed by the fact that React would just re-render the components that read changes anyway, this was a monumental step forward in making these systems debuggable and consistent. Over the next several years as algorithms became more refined we'd see a trend towards more pull based semantics.

Conquering Leaky Observers

Fine-grained reactivity is a variation of the Gang of Four's Observer Pattern. While a powerful pattern for synchronization it also has a classic problem. A Signal keeps a strong reference to its subscribers, so a long-lived Signal will retain all subscriptions unless manually disposed.

This bookkeeping gets prohibitively complicated with significant use, especially where nesting is involved. Nesting is common when dealing with branching logic and trees as you'd find when building UI views.

A lesser-known library, S.js (2013), would present the answer. S developed independently of most other solutions and was modeled more directly after digital circuits where all state change worked on clock cycles. It called its state primitive Signals. While not the first to use that name, it is where the term we use today comes from.

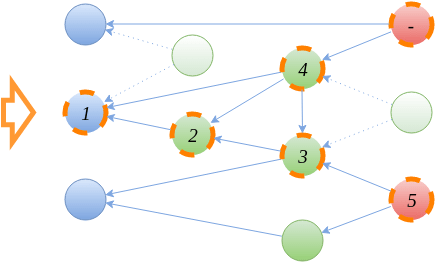

More importantly, it introduced the concept of reactive ownership. An owner would collect all child reactive scopes and manage their disposal on the owner's own disposal or were it ever to re-execute. The reactive graph would start wrapped in a root owner, and then each node would serve as an owner for its descendants. This owner pattern is not only useful for disposal but as a mechanism to build Provider/Consumer context into the reactive graph.

Scheduling

Vue (2014) also has also made huge contributions to where we are today. Besides being in lockstep with MobX with advances in optimizing for consistency, Vue has had fine-grained reactivity as its core since the beginning.

While Vue shares the use of a Virtual DOM with React, reactivity being first-class meant it developed along with the framework first as an internal mechanism to power its Options API to, in the last few years, being front and center in the Composition API (2020).

Vue took the push/pull mechanism one step forward by scheduling when the work would be done. By default with Vue all changes are collected but not processed until the effects queue is run on the next microtask.

However, this scheduling could also be used to do things like keep-alive(preserving offscreen graphs without computational cost), and Suspense. Even things like concurrent rendering are possible with this approach, really showing how one could get the best of both worlds of pull and push-based approaches.

Compilation

In 2019, Svelte 3 showed everyone just how much we could do with a compiler. In fact, they compile away the reactivity completely. This is not without tradeoffs, but more interesting is Svelte has shown us how a compiler can smooth out ergonomic shortcomings. And this will continue to be a trend here.

The language of reactivity: state, derived state, and effect; not only gives us everything we need to describe synchronized systems like user interfaces but is analyzable. We can know exactly what changes and where. The potential for traceability is profound:

Marvin Hagemeister ⚛️@marvinhagemeist

Marvin Hagemeister ⚛️@marvinhagemeist I think this one if the main reasons why any signals-based approach is better than hooks. It enables additional debugging insight which is not possible with hooks like exactly showing you *why* a piece of state updated.

I think this one if the main reasons why any signals-based approach is better than hooks. It enables additional debugging insight which is not possible with hooks like exactly showing you *why* a piece of state updated.

Planning to add a similar visualization to our DevTools too twitter.com/thetarnav/stat…09:36 AM - 14 Feb 2023thetarnav. @thetarnavRelease day for @solid_js devtools! 0.21.0 adds an essential way of inspecting reactivity: a Dependency Graph — it will display current (direct and indirect) sources and observers of the selected signal or computation https://t.co/oFNeKHMTzj https://t.co/cyDpdZmG1s

If we know that at compile time we can ship less JavaScript. We can be more liberal with our code loading. This is the foundation of resumability in Qwik and Marko.

Signals into the Future

Pawel Kozlowski@pkozlowski_os

Pawel Kozlowski@pkozlowski_os Signals are the new VDOM.

Signals are the new VDOM.

There is explosion of interest: many people are trying things. This will let us explore the space, try different strategies, understand and optimize things.

Not sure what we are going to settle on in the end, but this collective exploration is great!20:41 PM - 24 Sep 2022

Given how old this technology is, it is probably surprising to say there is much more to explore. But that is because it is a way of modeling solutions rather than a specific one. What it offers is a language to describe state synchronization independent of any side effect you'd have it perform.

It would seem unsurprising perhaps then that it would be adopted by Vue, Solid, Preact, Qwik, and Angular. We've seen it make its way into Rust with Leptos and Sycamore showing WASM on the DOM doesn't have to be slow. It is even being considered by React to be used under the hood:

Andrew Clark@acdlite

Andrew Clark@acdlite We might add a signals-like primitive to React but I don’t think it’s a great way to write UI code. It’s great for performance. But I prefer React’s model where you pretend the whole thing is recreated every time. Our plan is to use a compiler to achieve comparable performance.14:34 PM - 17 Feb 2023

We might add a signals-like primitive to React but I don’t think it’s a great way to write UI code. It’s great for performance. But I prefer React’s model where you pretend the whole thing is recreated every time. Our plan is to use a compiler to achieve comparable performance.14:34 PM - 17 Feb 2023

And maybe that's fitting as the Virtual DOM for React was always just an implementation detail.

Signals and the language of reactivity seem to be where things are converging. But that wasn't so obvious from its first outings into JavaScript. And maybe that is because JavaScript isn't the best language for it. I'd go as far as saying a lot of the pain we feel in frontend framework design these days are language concerns.

Wherever this all ends up it has been quite a ride so far. And with so many people giving Signals their attention, I can't wait to see where we end up next.