Writing dirty tests is similar to having no tests. The tests must change as the production code evolves. The dirtier the test, the more challenging it is to change them. Therefore, it’s vital to write clean tests and code.

Clean code always looks like it was written by someone who cares. There is nothing obvious you can do to make it better. — Michael Feathers

However, it looks like the test code is not considered the ‘real code’ and so is not labeled ‘dirty tests’.

In this session of the Testμ Conference, Gil Zilberfeld, CTA & CEO at TestinGil, collaborated with Anmol Gupta — Senior Product Manager at LambdaTest, to talk about concrete examples of anti-patterns in tests and how to clean them.

Below are the key takeaways from the session.

What makes code clean?

How do clean code principles apply to tests?

Code smells in tests.

Refactoring patterns in test code

Let’s explore more in this session!

Gil starts the session by explaining test and production code are the same thing and that we should apply the same standards to them. But it seems like we won’t do that!

Why is it important to write clean tests and code?

He provides a few different reasons why writing clean tests and code is crucial.

We know the real code, but it’s not like real code as it goes into production and is used by real users. We don’t consider ourselves real users, although we know we will be the users of this code.

There’s an evolution of code in which tests can be different because when we write a test that passes, it goes back in our mind to somewhere else, and we probably think we’ll never see that one again. We know we will, but we are focusing on the next test and forgot about the one that already passed.

It’s our perception of the differences between the code and how real it is. Access, like whether we go back to test, and if you think about it, we go back to production code. Test code mostly passes unless they’re broken or fragile, regardless of how you want to talk about them. We usually don’t go back until they break. Again we do some kind of separation between the two types of code, like action code.

Ultimately, we need to think about these things differently, and unless we do these same things, we can apply different standards.

Code that works over and over again

According to Gil, we want our code that works over and over again regardless of your method of development, whether agile or waterfall.

As developers, we like to work on new stuff but going back to something that worked before but now doesn’t work is a kind of a backward step. Keeping code clean allows us to create new stuff repeatedly and reduces the time spent on the old stuff. If we could read the code, we would spend less time on it and then move back to the new stuff.

So keeping code clean and tests is like respecting the time of future me or you. We can translate that into readability, maintainability, or anything but going back to the goal of working code over and over and over again translates to how much time and effort we put in and invest now to free some time in the future.

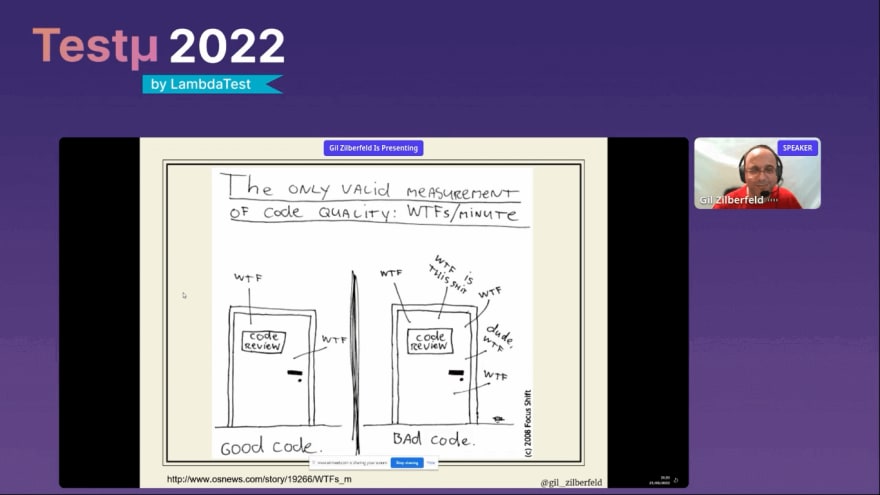

Good vs. Bad code

He then describes what good vs. bad code looks like.

Both good and bad codes are different as most of the code reviews are done not in the same room but through pull requests which is not a thing. When we review code, we see it from a different angle because the person who wrote it created the most magnificent code you ever created; otherwise, you wouldn’t say that it’s done. If I write and review the code, it’s excellent to ship it to let other people view it and share their feedback.

He then lists a few famous quotes about clean code.

Clean code is simple and direct. It should be written like prose — Grady Booch.

Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand — Martin Fowler.

What makes the tests clean?

Gil shares some aspects that make the tests clean. These are as follows.

You need to show some intent on how to use a code and what is expected when it is used in a scenario.

Tests should be focused on something. For example, we run the code in unit testing and perform some assertions.

Do exactly what they say.

Abstract implementation details.

Code smells in tests

Gil then went to explain code smells. When you’ve done a lot of coding, there are code smells. These are not problems functionally, but they will create hurdles for you as you proceed later.

There are a few patterns that have a name and usually apply for clean code or unclean code.

God class and methods.

Comments.

Uncommunicative names.

Embedded constants.

He then demonstrates a dirty test example of the controller of a calculator in Java language and how to make it clean utilizing a unit test framework.

In a nutshell, a great test doesn’t have any dissimilarity or difference in the standards between the test code and production code. — he added.

Time for a Q&A session!

How do I prevent unknowingly duplicating the code?

**Gil: **Usually, you’re the one who adapted the code, but in the code application, you find it in two ways. One is through regular reviews, where people will tell you who has seen this code elsewhere. There are tools to look for some code applications for patterns, not just exact code applications.

What are the other patterns that can be utilized, similar to your example of builder patterns in test automation?

Gil: In design patterns, we use a singleton; sometimes, we call it the evil singleton. For example, if you’re going to initialize the database as part of your tests, you will do it once for the rest of the test in your suite. So, it’s kind of a singleton. Then you can look up and see where patterns exist and relate to actual code. Tests are going to be in the same standards.

I believe everybody has their style of writing code, so how do we engage in the practice of writing it clean?

Gil: It’s not about clean coding. It’s a common team thing, so everyone has their styles, and if you are doing a code review for someone, you should think when you’re doing a review, and you want to say, well — this thing looks wrong. Does it look wrong just for me because I would have written it differently, or is this the way we want everyone to write code? You need to say these are the kinds of things that are important to fix and teach everyone about it. I think this should be the result of the code review and test review.

Is it sometimes easier to just delete tests and then rewrite them from scratch rather than try to improve what’s already there?

Gil: First of all, yes, and it’s true for code. There’s a deeper meaning in that. It was probably going to be easier because the tests were written not yesterday but a year ago, so trying to get into the mind of somebody else’s code is like a very big endeavor to do it correctly and right on the first time. Therefore, deleting and writing from scratch is usually easier and simpler.

What are some good practices we should follow during code review?

Gil: People usually say — you’re not your code. It’s true, but the people doing the reviews are not the owner of the code, so it’s code. It can be replaced or written in different ways.

So the first thing is to be nice and the second thing is to think about whether it is important, so everybody can learn how to do it not because of how you would write it as when you do this kind of distinction, people start thinking about if they can still read it that’s not a big problem. Therefore, if you keep these things in mind, everybody can read the important and unimportant stuff.